“Make No Small Plans” is the Summit Series motto, and it doesn’t. The “Burning Man meets Davos” event company has bought a mountain, rented cruise ships and, this week, is taking over Los Angeles.

If you can get an invite, Summit could see you learn to free dive or meditate, watch Quentin Tarantino or Kendrick Lamar debate art, take a class on polyamory or protest organization, rock out to Thievery Corporation, hear Google’s Eric Schmidt talk business or Erin Brockovich talk social justice, eat a gourmet meal and then dance until sunrise.

Summit was designed not around a traditional conference theme, but to stoke camaraderie around curiosity. “We’re in the age of the polymath,” says Summit co-founder Jeff Rosenthal. “People are into everything. They’re wakeboarders who are also engineers who enjoy painting in their free time.” His co-founder, Elliot Bisnow, calls it a community for “Multi-disciplinary thought leaders with the intention of shaping the world.”

Now it’s trying to turn that intention into concrete impact so Summit isn’t just a party for the privileged.

Experiencing Summit is an exercise in cognitive dissonance. You’re gathering with an exclusive, elite community while riffing on ideas to help the impoverished. You’re flying to a remote destination like Tulum, Mexico or living it up on a gas-guzzling cruise liner while championing the environment. And you discuss gender inequality as guys sometimes ogle women at the hot tub. The company has been accused by female attendees of porting in Instagram models in the past, however there’s never been substantiated evidence of this, and the membership vetting committee is led by women.

Over the years, though, Summit has increasingly striven to give attendees ways to give back or at least offset their guilt.

A mile-long dinner table on Powder Mountain, Utah at Summit Outside. Image Credit: Ian Matteson

That’s part of the reason this week’s event is happening in the center of LA, which is much more accessible than a cruise through the Bahamas or a Utah ski mansion. It’s why Summit has finally focused on hitting an even gender ratio, improving ethnic diversity (it’s got a ways to go) and offering scholarships for artists and activists who can’t afford tickets that typically start at several thousands of dollars. And it’s what gave birth to the company’s nonprofit arm, Summit Institute.

Summit has helped raise $2.5 million to protect one million acres of land in Sarara Kenya, and partnered with The Nature Conservancy to create a 77-square-mile reserve off the Bahamas where its cruises tour. It’s also raised $50,000 for the Fish Face program that uses facial recognition software to determine which species are being overfished.

It’s easy to write-off Summit as merely a playground for the prosperous that’s looking to improve its image. But my interviews with the team gave me the impression that it’s earnest in its drive to utilize this wealth and passion, pushing Summitters to put their money where their woke mouths are. There’s even a session this weekend bluntly titled “Now what? Turning conversation into action.”

From base camp to summit

“I didn’t get invited to any gatherings,” Bisnow tells me about how Summit Series got started. The 22-year-old real estate newsletter author’s answer to feeling uncool? Create his own aspirational event that people he admired would attend. So in 2008, Bisnow, Rosenthal, Brett Leve, Jeremy Schwartz and Ryan Begelman created what would become Summit Series with their first assembly in a Park City, Utah.

Just 19 people showed up.

Summit co-founder Elliott Bisnow kicks off the weekend at Summit At Sea

“We come from nothing, and it was just us cold-calling people for a ski trip,” says Rosenthal. But by fostering an atmosphere for ambitious ideas about both personal and global enlightenment, momentum grew.

Bisnow and the team charged another event in Playa Del Carmen, Mexico on credit cards, and a circle of rising stars in the startup world began to coalesce. That’s when the Summit crew was invited to produce an event at the White House where they brought 35 entrepreneurs, like Twitter co-founder Evan Williams and Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh, to explore economic issues with senior Obama staff.

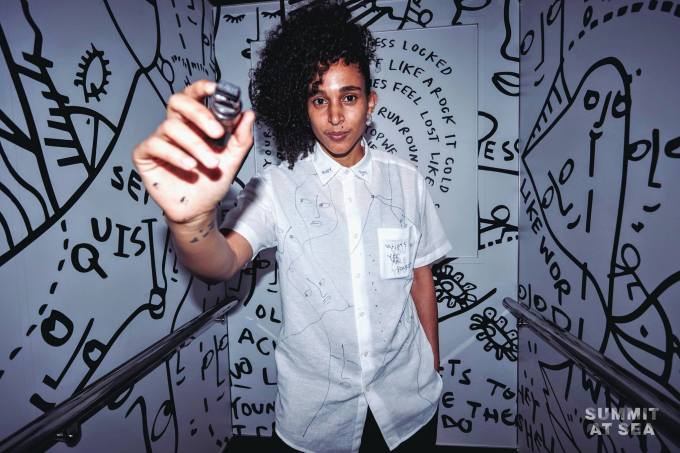

Shantell Martin illustrates the elevators on Summit At Sea

That set Summit on an audacious path to being more than a vacation company. “There’s this underlying hope to create community that has influence, that has access, and that has the ability to affect change,” says Shantell Martin, one of Summit’s eventual artists-in-residence. Her notebook doodle-style illustrations would later turn the chintzy Summit At Sea cruise ship elevators into immersive daydreams.

By 2010, Summit was organizing fundraisers with Bill Clinton at the Def Jam records co-founder Russell Simmons’ NYC mansion, and throwing a three-day event in Washington, D.C. While attendance had grown to 750, Summit was meticulous about curating its core clientele. Most were either personally invited, or had passed screening interviews after being referred by an existing member.

Quentin Tarantino and Kendrick Lamar speak about art on Summit At Sea. Image Credit: Amy Harris

But entry doesn’t come down to money raised, companies sold or headlines grabbed. Bisnow says Summit is for, “first and foremost, really nice people. People living their passions, doing good work in the world. It doesn’t just mean running a business,” he explains. “You can be an ‘intrepreneur’ inside of any company, you can be working with the sciences or arts, excelling at teaching . . . we want to build a community of good-hearted people.”

That creates an extremely unique ambiance at Summit events where people genuinely want to meet each other. There’s a sense that everyone has some special skill or experience worth hearing about, so it’s common to strike up conversations with strangers. Yet talk usually focuses on excitement and impact rather than job titles and name-dropping.

The sense of camaraderie was most apparent in Summit’s hey-day, with its first 1,500-person Summit At Sea in 2011 where big-wigs let their guard down to dance on the deck through dawn. 2013’s Summit Outside saw 700 people glamp out in tents and all sit down for a hillside sunset dinner at a single table more than a mile long. There I huddled under the stars discussing gay rights activism through song with one of the playwrites of Avenue Q before he sang his new tune over an instrumental saved on his phone. When a stray ad exec bro mechanically asked who people worked for, they were chided for making the moment transactional.

Summit Outside was the triumphant inauguration of the organization’s new home base on Utah’s Powder Mountain that it had bought for $40 million with help from some wealthier members who are now building homes there.

Summit Outside’s mile-long dinner table on Powder Mountain

No internet meant few distractions for a notoriously wired set who traded boardrooms for paintball and horseback riding in the wilderness. The band Poolside played poolside as Summitters swayed to the lazy dance rock, before night fell to the sounds of OutKast rapper Big Boi. Attendees were told they were the change-makers, responsible for delivering the empowerment vibration back to society. Cynicism was at a minimum.

“Show love to the startups and don’t fanboy the big-timers”

This Summit rule became more and more critical as the community tried to scale. The disparity between speakers and attendees widened, and some big-wigs would get mobbed between sessions while snubbing those without fame.

At 2015’s Summit At Sea, there were 4,000 guests on board, and rips in the seams began to show. Summit had become a known spectacle and status symbol, akin to a private Coachella. As friends-of-friends-of-friends were admitted, it was more about who you knew than what you’d created.

An oversubscribed wellness panel packs in attendees at Summit At Sea. Image Credit: Daniel Fox

Summitters began to slip from being “like-minded” into obvious homogeneity. “We’re all white dudes. We know it,” Rosenthal says of the founding team. “It’s all referrals. There is a limitation to that.” New members mirrored the core, concentrated around Caucasians from NY, SF and LA.

One of Summit’s most popular perennial speakers, relationship guru Esther Perel, tells me, “A lot of people didn’t feel particularly safe on the boat. Not women, not people of color. You can feel very small if you’re not a big name.” The natural excess of the Vegas-style cruise liners seemed gaudy when contrasted to the organization’s intentions.

Luckily, Rosenthal says, “We find criticism is the greatest gift.” He understands that “if we do things that aren’t aligned with the culture even a little bit, then everyone is active participant in that. Any community can lose its cool.”

Relationship guru Esther Perel calls on the crowd of Summit Outside to go make change

So Summit stepped up. It implemented more scholarships and discounts to improve socioeconomic diversity, selling higher-priced luxury accommodations to the rich in order to subsidize lower-priced options. It tried to internationalize the membership. It sought top female entrepreneurs so that now Bisnow says “all the events are 50-50 men and women or very close to that.” It improved accountability and reporting structures to weed out creeps. And it partnered with an anti-recidivism program to bring formerly incarcerated juveniles aboard the boat. Some “had never left the country. None had ever been on a cruise ship,” says Rosenthal.

The strides were evident on 2016’s Summit At Sea trip, which felt less boozy and sexually charged with leaders from a wider range of backgrounds.

Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors discussed racial inequality, and civil rights heroes like Dolores Huerta and LeDonna Harris spoke about carrying on the fight in the wake of Donald Trump’s election. Held November 9th to 11th last year, the boat became a place to commiserate Hillary Clinton’s loss and unite for the upcoming struggle.

John Legend (left) and Harry Belafonte speak at Summit At Sea

Rather than a place to escape and forget the real world, Summit was returning to its roots of hoping to change it. There’s still long way to go, though. “The problem is that the people who attend these diversity talks are the diverse people,” Martin notes.

One solution has been for Summit to launch a calendar of cheaper, smaller, more intimate events on Powder Mountain throughout the summers and winters. With fewer friends and programming options, attendees are better exposed to new people and the ideas Summit prioritizes. After hitting the slopes atop the hill or practicing archery and yoga at the bottom, attendees bond on the chairlift or by the fireside instead of raving to all-night DJ sets.

A more intimate Summit weekend at Powder Mountain

“I liked how ‘Kumbaya’ it was from the beginning. Most conferences give you the schedule, and say ‘here’s your networking break,’ “, sustainable fashion company Zady’s co-founder and Trail Mix Ventures founder Soraya Darabi tells me about her Summit experiences. “I’m a New Yorker and we don’t hug each other. But by the end of the weekend I was hugging strangers because I truly was inspired.”

From summit to society

Now the goal is spreading that sense of inspiration beyond the Summit goers and getaways. That includes using Summit’s homegrown social networking app to tie the community together after the events end.

While unticketed civilians can’t attend this weekend’s programming in LA, which the founders previously implied was part of the plan, hosting Summit in a big city for the first time in nearly a decade could make members feel more responsible to the world at large.

Alexa Meade paints Summit’s movement artist-in-residence Lil Buck before a dance performance on Summit At Sea

“If it can be a conduit for galvanizing people to think broadly about philanthropy, then there’s an opportunity if not a duty for them to do some altruism,” says Darabi. “What I’d love to see come out of Summit is measurable impact.” That could mean organizing post-event volunteering, more strongly soliciting donations and teaching members how to communicate the event’s philosophies to friends.

The weekend’s headlining talk will see Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos speak about charity with his brother Mark Bezos, who leads the education-focused Bezos Family Foundation. That’s a stern shift from Summit At Sea 2015’s big panel with Uber CEO Travis Kalanick laughing it up about the potential of self-driving cars… that we all know stand to replace millions of jobs.

“There’s definitely a larger purpose. I‘m not sure if they’ve reached it yet,” says Martin, who hopes for continued progress while commending Summit for its artist-in-residence program she thinks more companies should adopt.” Perel believes the founders have gotten the message. “They’re building an aspirational community that’s very steeped in quality of life, integrity, entertainment and high levels of self-expression,” she says.

“We want to have a really positive impact while we’re here on earth because life’s too short,” says Rosenthal. The Kool-Aid flows strong at Summit, that’s for sure. Still, a culture of in-person idealism, even if naive or with gaps, is a refreshing alternative to the exhausting trudge through Twitter snark and aimless clicktivism.

Summit is experiencing an offline parallel to Facebook’s own rocky evolution. Both have succeeded in creating community. But connecting people isn’t enough. Community can be squandered, and shallow interaction can drain energy from making real impact. It can’t be enough to feel good without doing good. The foundation is there, though.

Summit’s toughest climb will be ensuring awareness and sincerity are harnessed for action. Bisnow calls it “a learning festival, the ultimate post-college education.” But after nine years, Summit seems ready to graduate. “What’s the reason that Summit should exist? To date it’s all been about connecting people and having a great experience,” Bisnow concludes. “Okay. Now, on a really big scale, how do we activate our community about the issues of our time?’

Summit movement artist-in-residence levitates above the Utah mountains