We’re taking a look at the IPOs of tech’s biggest players, the firms that we call the Big 5. We started with Amazon. Next up on our list is Google, the search and advertising giant.

Google, now part of Alphabet, a holding company it created, went public in 2004. At the time, the firm frankly told investors in its founders’ letter that it was “not a conventional company,” and it did “not intend to become one.”

For Google, the unconventional attitude worked, and it worked well. But before its IPO more than 10 years ago, the company’s future was hardly certain. The climate that Google went public under is almost hard to imagine: In the pre-unicorn era, the most valuable internet company wasn’t even worth $50 billion (as we’ll see). Today, there are private tech companies worth more than that.

In the end, Google went public worth around $23 billion. That number should sound familiar, as it is a mere $1 billion from Snap’s own IPO value set earlier this year.

To understand Google’s debut, we have to turn the clock back to 2003. Let’s go.

2003

Before its IPO, Microsoft and Google reportedly discussed doing something together. Details are vague, but Ars Technica published some interesting details in late 2003, the year preceding Google’s debut.

Leaning on Ken Fisher’s contemporaneous reporting, here are the words used to describe the potential for a Microsoft-Google link:

Sources are saying that Microsoft was previously courting Google, pursuing options ranging from a kind of merger to an outright takeover. It appears that their overtures failed to materialize any deal, so now the Redmond will have to wait; Google is headed in the IPO direction, and if there’s a merger to be had, it’s likely going to be with a post-IPO Google.

The same Ars Technica piece goes on to report that, yes, Google “appear[ed] to be in preparation to convert to publicly-traded status,” a result that would be “huge.” That wound up being incredibly correct.

(For fun: In 2006, Microsoft launched Windows Live search. In 2007, it was renamed Live Search. It was later rebranded Bing in 2009.)

How close Google and Microsoft ever got to a deal is now immaterial, because, on April 29, 2004, Google dropped its first S-1.

Google up close

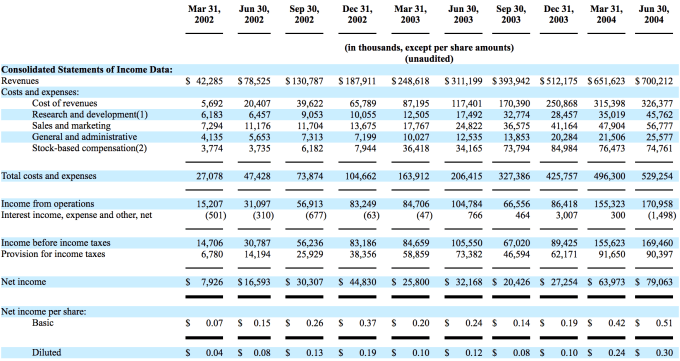

The firm’s initial S-1 would later be supplemented with another quarter’s financial results as the IPO came together during 2004, but it’s worth noting that, in the original document, the company reported steep growth and growing GAAP profits.

The company’s later filings have an even fuller picture of that expansion, as they included the quarter ending June 30. Here’s the full set of numbers:

As you can see, Google was growing at a tremendous clip, regarding its revenue and profit, when it filed. The firm’s first to second quarter sequential growth rate was just 7.5 percent, but the year-over-year comparison Google set in the second quarter of 2004 calculates to a 181.6 percent growth rate.

And as Google’s revenue grew, its net income grew, as well. In the first half of 2004, Google’s revenue totaled $1.351 billion, from $559.8 million in the first half of 2003. Profit grew to $143.0 million in the first two quarters of 2004, from $58.9 million during the first six months of 2003.

(Keep in mind as we go on that Google winds up being worth less than Snap at its IPO.)

Google had something else at the time that we’d be remiss to mention before diving into the pricing saga that surrounded its IPO. The firm had a bucket of cash — nearly $550 million — and limited liabilities.

It isn’t hard to guess from the numbers that Google was growing quickly under its own steam — the search engine didn’t really need the IPO proceeds to fund its business. Doubling down on that point, the founders’ letter is illustrative again: “Google has had adequate cash to fund our business and has generated additional cash through operations.” Correct.

Pricing dance

What was Google worth? The final number was hard to uncover at the time it went public.

To wit, Google’s first S-1 indicated that the firm wanted to raise as much as $2.72 billion in its IPO. Later filings pushed that number as high as $3.989 billion, a valuation that entailed a per-share price of $135.

Google’s IPO aspirations were eventually cut down to allow the firm to cross the finish line. The following New York Times passage from July 27, 2004, describes the company’s mid-summer 2004 pricing moves:

The popular Internet search company, which is attempting to sell shares to the public in an unconventional auction, said in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission yesterday that it expected its shares to sell for $108 to $135 each.

That would value the company at $29 billion to $36 billion, putting its market value just below the $38 billion value of Yahoo, a larger and far more mature Internet company. The most valuable Internet company, eBay, is worth $49 billion.

This analysis is interesting for a few reasons:

- Google failed to maintain that hoped-for price range. The company’s final IPO price, $85, was under range.

- Yahoo was worth $38 billion.

- The largest internet company, at that time, was worth less than Uber is today.

A different era.

Regardless, Google went public at $85 after cutting the number of shares offered to 19.6 million from nearly 25 million. The company’s valuation wound up at $23 billion.

Doing some quick math, at $23 billion, Google priced at a trailing revenue multiple of just over 10. That’s high by today’s SaaS standards (Google wasn’t SaaS as we think of it), but it becomes incredibly cheap by modern standards when you realize that you can calculate Google’s PE ratio at the time (around 120). It was already profitable, and profitable revenue is worth more than unprofitable revenue — all else being held equal.

Despite the fact that Google would have been wildly healthy by today’s standards, it isn’t hard to find naysayers from the time. This lede, for example, sticks out:

Google said Wednesday it will go public at $85 a share, paving the way for the widely awaited but troubled stock offering to finally stumble to market on Thursday.

Good heavens, CNN Money!

The point, however, was that Google thought it was worth more than the market did at the time, hoping for that $135 per share and ending up with just $85. In the end, both parties were wrong. Google was likely cheap at $135 per share, the upper end of its highest range.

But IPOs are both magic and math, something that Google took to the next level with how it went public.

The Dutch auction

Google, not content to do things along normal lines, went public using a Dutch auction. If that sounds unfamiliar, don’t feel bad. Aside from Google, I can’t recall a company of real note that has used a similar process since.

And, as we’ll see, perhaps there’s a reason for that. Regardless, back in 2004, the company’s Dutch auction was big news. Forbes quoted a money manager at the time who called the choice “definitely the biggest story” of the IPO.

That wasn’t correct; the strength of Google’s core business was the biggest story, but the quote shows how odd Google’s call was at the time.

The same Forbes piece does a fine job detailing what a Dutch auction entails:

In a Dutch auction, a company reveals the maximum amount of shares being sold and sometimes a potential price for those shares. Investors then state the number of shares they want and at what price. Once a minimum clearing price is determined, investors who bid at least that price are awarded shares. If there are more bids than shares available, allotment is on a pro-rata basis–awarding a percent of actual shares available based on the percent bid for–or a maximum basis, which fills the maximum amount of smaller bids by setting an allocation for the largest bids.

As CNBC noted in 2014, the model may “[t]ake the short-term gains away from Wall Street and big money and give at least some ownership” to regular people. However, Google’s use didn’t help Dutch auctions take off.

The CNBC piece makes two arguments that are persuasive as to why Dutch auctions didn’t pick up a host of fans following Google’s use. First, “[similar] auctions are risky,” especially if you might need some help driving demand. That isn’t a problem for the hottest IPOs, but they make up only a fraction of the total.

The piece goes on to argue:

The second reason is that Google’s offering wasn’t a real auction, but more of a hybrid. After all, there was clearly enough investor demand to price the stock at closer to $100, because that’s where the stock opened, but at the last minute lead underwriters Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse dropped it to $85. The low end of the expected range had been $108.

Still, after all the stress and pricing work was over, Google opened well and took off.

Hindsight is 20-20 (and very expensive)

Google had a good first day’s trading, bumping up 18 percent or so to just over $100 per share from its $85 starting point. The company’s all-time intraday low was $95.56, and its all-time lowest close was $100.01, according to a 2008 report.

After finally getting its IPO out the door, Google did well, and it has continued to do little else. The firm is now worth around $650 billion, second only to Apple. But placing second out of the Big 5 wasn’t a sure bet back then.

“It’s still expensive at these levels,” said Will Dunbar, managing director with Core Capital Partners, a venture capital firm with no stake in Google. “There will be substantial competition in the near future and that’s one of the things that gives me pause about the price.”

Janco’s Pyykkonen adds that he was hearing it was difficult for traders interested in short-selling Google to find shares to borrow from the banks and brokers involved in the auction. […]

And according to an informal poll on CNN/Money, 85 percent of more than 23,000 respondents said that they did not plan on buying shares of Google once it began trading.