In its latest paper, the Facebook AI Research (FAIR) team dropped some impressive results for its implementation of a modified convolutional neural network for machine translation. Facebook says it has achieved a small bump in accuracy at nine times the speed of traditional recurrent network models. And to complement its research, the company is releasing its pre-trained models on GitHub, along with all the tools needed to replicate the results on your own.

When most of us think of machine translation, we think of Google Translate (sorry Facebook and my 8th grade Spanish teacher). But while that is certainly the most well-known implementation, Facebook relies on the technology extensively for translating posts on News Feed, among other uses.

In these use cases, accuracy is important to a deliver competitive experience, but arguably speed is even more important to Facebook. With nearly two billion users, every incremental improvement in speed is magnified. And Facebook isn’t just promising an incremental improvement, they’re promising an improvement of 900 percent.

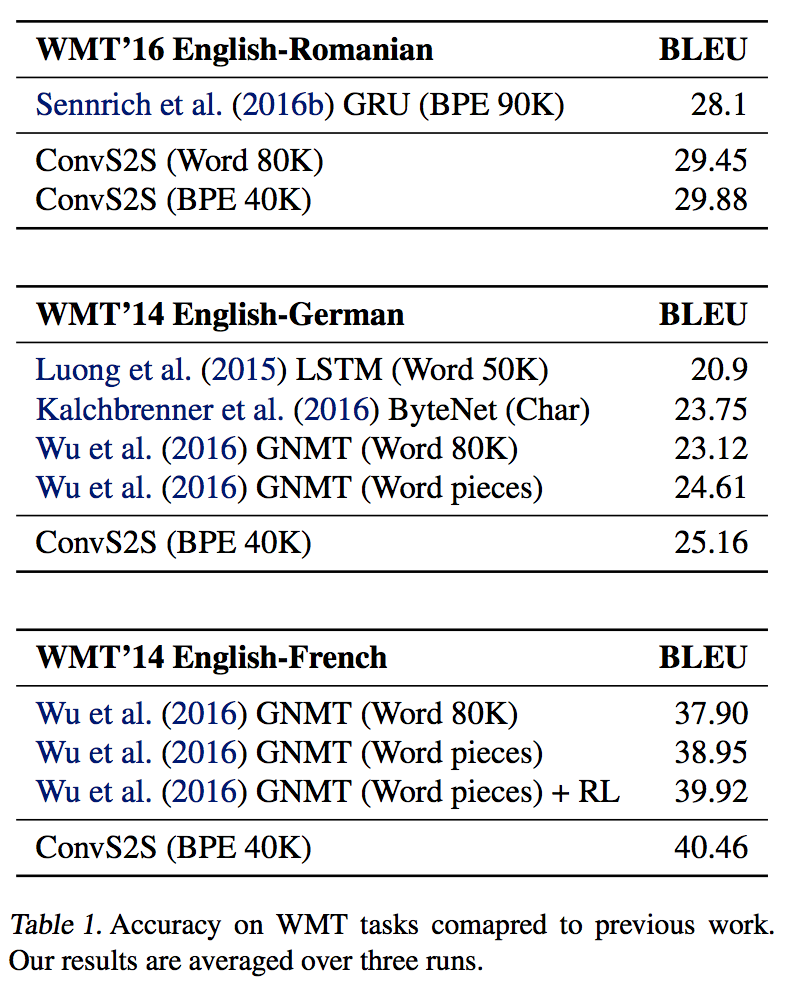

In terms of accuracy, the gold standard for evaluating the quality of machine translation is BLEU, bilingual evaluation understudy. Facebook benchmarked its sequence to sequence convolutional approach on three tasks — translating English to Romanian, translating English to German and translating English to French.

David Grangier and Michael Auli, two of the authors on the paper, explained to me that these tasks weren’t selected because they are the hardest languages to translate, but because they are the most competitive and others have already achieved impressive BLEU scores using alternative methods.

Based on these numbers, applying ConvNets to machine translation is a worthy pursuit, but it’s worth stepping back a bit to explore why recurrent nets are typically used over ConvNets for translation in the first place. Recurrent networks take into account time series information, which makes them ideal for handling sequential tasks — reading left to right is a great example of this.

ConvNets, on the other hand, have risen in prominence in recent years because of how useful they are for analyzing visual information. They process information simultaneously rather than sequentially, which presents barriers if you want to use them for machine translation. To make it work, Facebook implemented what it calls “multi-hop attention.”

Machine translation is a two-step process. As humans, we take for granted the process of understanding a sentence in our own language, but machines have to first put resources into this before they can output to another language.

Another thing we don’t realize is that everything we do is governed by probabilities. “Bait” for example can be both a noun and a verb, and when we evaluate a sentence we are subconsciously assigning likelihoods that help us interpret meaning. This requires us to reference other parts of a sentence at different times to develop understanding.

In something of a twist on this process, Facebook’s multi-hop takes advantage of the simultaneous nature of ConvNets to allow machines to reference different parts of text to build understanding during encoding. Once this is done and a vector representation is created, a translation can be outputted one word at a time until it’s complete.

Grangier and Auli believe their models can be engineered to do more than simply machine translation. Their ConvNet could be used in any scenario where a computer needs to understand text and express something, so this could include summarizing text or even interpreting a reading and then asking questions.

Both reinforcement learning and adversarial networks have the potential to improve upon the results achieved by Facebook — each of these could become a standalone paper. Additionally, the team hopes to further experiment with the applications of multi-hop attention.