The hot air around young and savvy tech startups is not going anywhere, despite dark prophecies that saw 2016 as the “winter is coming” year.

Snapchat and Airbnb are warming up on the sidelines of an IPO, BuzzFeed, Palantir and Uber are snatching hundreds of millions of dollars every couple of months and young startups with no revenues and almost no users (such as Houseparty) raise tens of millions of dollars from top VCs.

The tech bubble is focused around the automotive industry, with valuations per employee at a staggering $10 million. These young startups raise multi-million rounds even before showing a prototype and spark the rapid migration of talent from one startup to the next. Deals are quickly concluded, a sign of high demand for startups, and it is clear that the tech bubble is here to stay for a while, driving up valuation of lower-tier of startups.

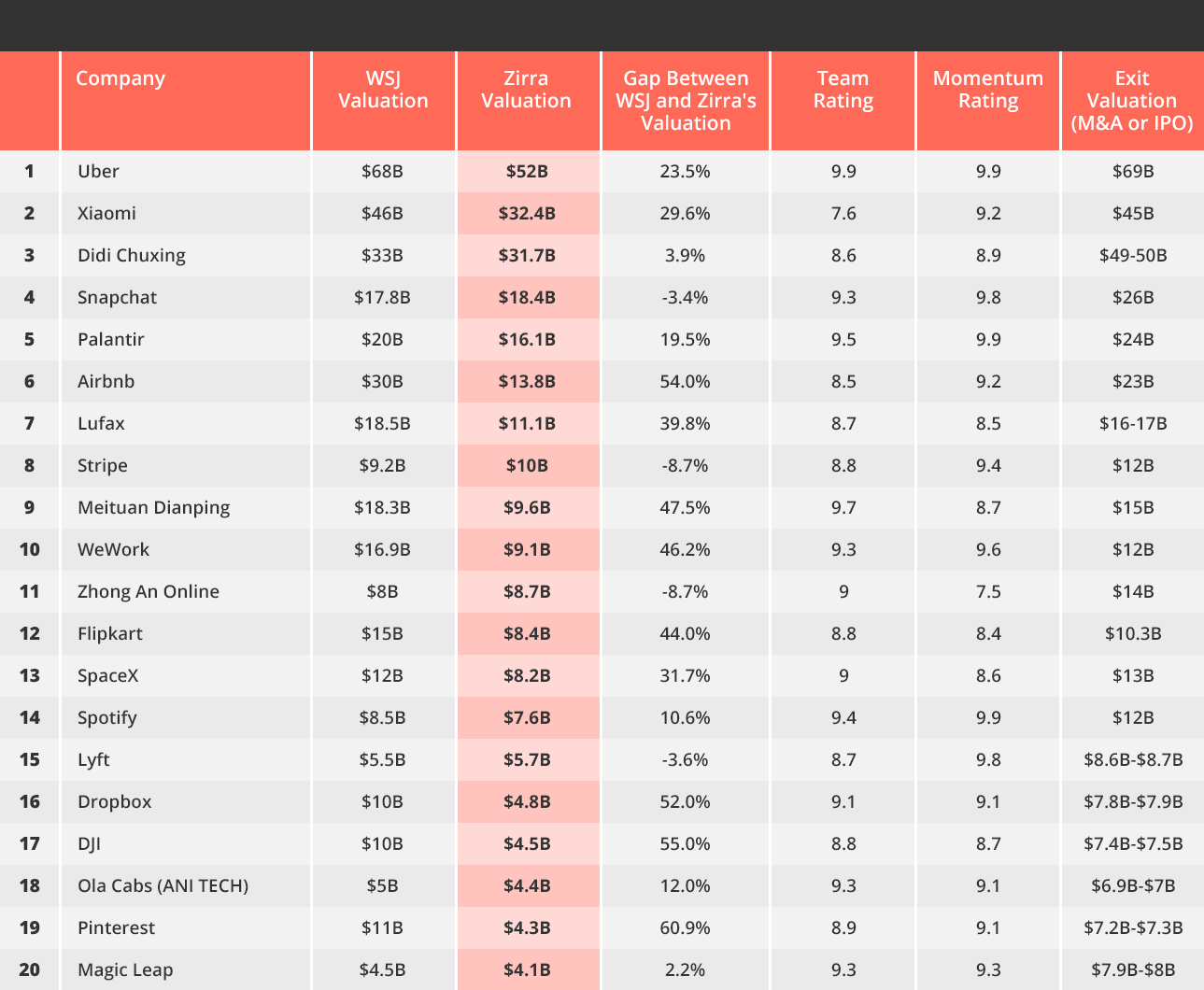

But first, let’s take a look at the “real” valuation of unicorn companies, or what their value should have been if they were already publicly traded. According to our formula, which uses 1,200 comparable private company histories, as well as dozens of current public signals — ranging from web traffic trajectories, investment history, employee growth, Google searches and customer reviews — the top 20 unicorns are already overvalued by an average of 27 percent.

Zooming in on specific cases, some of the valuations we estimated using public data were even much lower. We estimated Airbnb’s valuation at $13.8 billion, about half of its commonly estimated price tag of $25-$30 billion. Pinterest, according to our formula, can be priced at $4.3 billion, ~61 percent below the common $11 billion valuation. Even WeWork, the real estate-meet-startup exploding giant, is estimated by our formula to be valued at $9.1 billion, ~46 percent lower than market common value, and SpaceX at $8.2 billion is ~32 percent below the accepted threshold.

Zirra’s 20 most valued private tech companies. Source: Zirra

So what makes private tech companies rack up such high valuations? Here are the main reasons we found — some trivial, some more significant.

When negative cash flow meets perpetual up rounds. To capture market share and manage regulatory campaigns, giants such as Airbnb and Uber need a constant flow of cash. As they add more and more investors, companies need to allocate new preferred shares that artificially pump up valuation. It is enough to have just one stubborn early investor in round A or B demand preferred stocks with extraordinary terms to cause every following investor to demand similar terms, or higher. This, in turn, brings companies to demand higher and higher valuations when raising new money or at IPO.

Bullish public markets. After a tiny cough at the beginning of 2016, the stock market rose to new peaks, bringing NASDAQ to its highest price in history — even higher than before it plunged dramatically at the turn of the new millennium. Apple, Alphabet, Facebook and Amazon stocks are all enjoying good times, while Snapchat’s IPO in the first third of 2017 looks promising. A bullish stock market dictates a positive investment environment; as long as it rises, so too do the valuations of private tech companies.

Artificial valuation formulas and methods used by VC firms. A derivative of the previous factor, VCs value companies using pricing methods, passing up on the traditional methods of valuation that take into account discounted cash flow, growth and risk estimation. These relative methods use relative valuation, pricing companies as a result of similar public and private companies in the market. So, again, when the market is high, valuations of private companies soar.

Talk is cheap; money is even cheaper. Despite the recent increase, interest rates are still low, and alternative investment asset classes such as VCs and private equity are popular alternatives for “high return.” Despite a small decline, total VC investments in startups are still high compared to pre-2014 years. According to NVCA, U.S.-based VCs invested $69 billion in startups in 2014, $79 billion in 2015, and $56 billion up to September, 2016.

Large sums of money, in the hands of more and more investors (some of whom are seeking high risk and perhaps are not as professional as the veterans in the market), will lead companies to take advantage of the trend. In addition, dwindling of public markets in China and other parts of the world concentrates more funds in U.S. rising stars.

The herd has turned to a stampede. The me-too effect: Copycat and me too players provide the impression that the startup industry is bigger than it really is. It also allows second- and third-tier investors to nab companies that couldn’t impress top investors.

Cut-throat competition between VCs over the more attractive deals drives valuations through the roof and causes VCs to run a much looser due diligence process in order to quickly win deals. This, then, impacts every financial round thereafter and has a spillover effect on other companies, even if they are not as attractive. High demand from investors meets a relatively low supply of good investment opportunity, causing investors to quickly shake hands and open the checkbook.

The bubble will not continue forever. Sectors that used to be super hot such, as cloud computing or mobile apps, are not disruptive anymore, and in a few years AI and automotive will also lose their shine. It will still take quite a few years for all these innovative companies to meet real infrastructure and cultural change, and the innovation industry is about to crunch. When that happens, consumers will realize they don’t need so many me-too products around them, and as the interest rates begin to rise again and VC vintages are over, we may see valuations turn the current game much more “interesting” — or perhaps even a much less friendly term.