The Chinese government has passed new cybersecurity regulations Nov. 7 that will put stringent new requirements on technology companies operating in the country. The proposed Cybersecurity Law comes with data localization, surveillance, and real-name requirements.

The regulation would require instant messaging services and other internet companies to require users to register with their real names and personal information, and to censor content that is “prohibited.” Real name policies restrict anonymity and can encourage self-censorship for online communication.

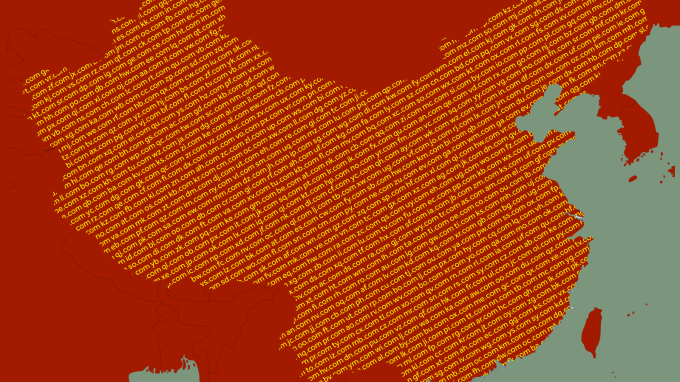

The law also includes a requirement for data localization, which would force “critical information infrastructure operators” to store data within China’s borders. According to Human Rights Watch, an advocacy organization that is opposing the legislation, the law does not include a clear definition of infrastructure operators, and many businesses could be lumped into the definition.

“The law will effectively put China’s Internet companies, and hundreds of millions of Internet users, under greater state control,” said Sophie Richardson, Human Rights Watch’s China director. HRW maintains that, while many of the regulations are not new, most were informal or only laid out in low-level law — and implementing the measures on a broader level will lead to stricter enforcement.

In addition to the censorship measures, the law lives up to its name with some new requirements for cybersecurity. Companies are required to report “network security incidents” to the government and inform consumers of breaches, but the law also states that companies must provide “technical support” to government agencies during investigations. “Technical support” is also not clearly defined, but could mean providing encryption backdoors or other surveillance assistance to the government.

The Cybersecurity Law also criminalizes several categories of content, including that which encourages “overthrowing the socialist system,” “fabricating or spreading false information to disturb economic order,” or “incit[ing] separatism or damage national unity.”

“If online speech and privacy are a bellwether of Beijing’s attitude toward peaceful criticism, everyone — including netizens in China and major international corporations — is now at risk,” said Richardson. “This law’s passage means there are no protections for users against serious charges.”