Garbage in, garbage out — that’s always been a rule of computing, and machine learning systems are no exception. These elementary AIs only know what we tell them, and if that data carries a bias of any kind, so too will the system trained on it. Google is looking to avoid such awkward and potentially serious situations systematically with a method it calls “Equality of Opportunity.”

Machine learning systems are basically prediction engines that learn the characteristics of various sets of data and then, given a new bit of data, assign it to one of several buckets: an image recognition system might learn the difference between different types of cars, assigning each picture a label like “sedan,” “pickup truck,” “bus,” etc.

Mistakes are inevitable: consider a BRAT or El Camino. Whatever the computer decides, it’s wrong, because it didn’t have enough data on this underrepresented type of vehicle.

The consequences of that particular mistake are likely to be trivial, but what if the computer is sorting through people instead of cars, and categorizing them for risk of default on a home loan? People who fall outside the common parameters are disproportionately likely to fall afoul of what the system learns are good bets from the rest of the data set — that’s just how machine learning operates.

“When group membership coincides with a sensitive attribute, such as race, gender, disability, or religion, this situation can lead to unjust or prejudicial outcomes,” wrote Google Brain’s Moritz Hardt in a blog post. “Despite the need, a vetted methodology in machine learning for preventing this kind of discrimination based on sensitive attributes has been lacking.”

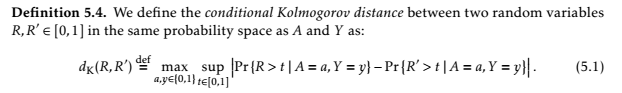

Hardt, alongside his colleagues Eric Price and Nathan Srebro, wrote a paper describing a way to avoid this kind of outcome. There’s a lot of stuff like this:

But the gist is this: When there’s a desired outcome and a possibility of one of those attributes incorrectly affecting someone’s likelihood of getting it, the algorithm adjusts itself so there is a similar proportion of those outcomes regardless of that attribute. It’s really no trouble for the computer — you train it so it values parity between non-relevant attributes.

You can get an intuitive sense of it with these interactive charts the team made. It’s not about goosing the numbers to be politically correct; the resulting model will actually be more accurate in its predictions. And if one of these attributes is relevant — say you’re calculating the likelihood of someone having this or that religion based on their location, or making medical predictions that differ between sexes — you just include it.

It’s a thoughtful line of inquiry for Google to be pursuing, and highly relevant as well, considering how machine learning is pervading so many industries so quickly. It’s important to be well aware of the limitations and risks of new technologies, and this is a subtle but important one.

The authors will be presenting their paper at the Neural Information Processing Systems conference — as good a reason as any to go to Barcelona.