Tatooine, is that you?

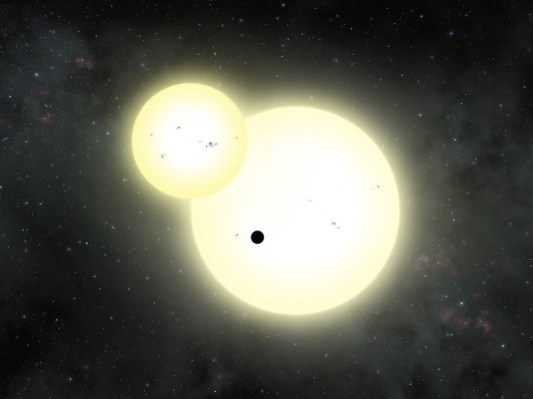

A team of astronomers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and San Diego State University has discovered a new exoplanet that orbits around two stars. What’s notable about this particular discovery is that it’s the largest planet in a double-star system discovered so far.

Known to astronomers as Kepler-1647b, the exoplanet orbits in the “habitable-zone” of its star, where liquid water could exist on the surface – an important ingredient for life to form. However, Kepler-1647b’s size is nearly identical to Jupiter, which means it is a gas giant and unlikely to host life as we know it.

Other than its size, however, the Tatooine-type system shares some similarities with our Earth-Sun system. At 4.4 billion years old, Kepler-1647b is about the same age of the Earth. Also, the two stars that the exoplanet orbits are similar to our sun, with one slightly larger and one slightly smaller than our home star.

The newly discovered planet is located about 3,700 light-years away from Earth and too dim to see in the night sky with your naked eye. Because it takes 3,700 years for light from the Kepler-1647b star system to reach the Earth, astronomers studying this system are seeing it as it existed 3,700 years ago.

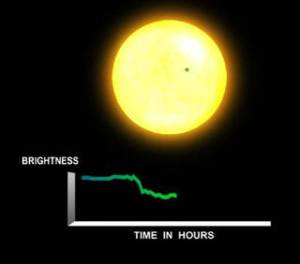

The Kepler Space Telescope, which launched in 2009, can detect planets around other stars using the transit method. With this strategy, astronomers look for dips in brightness from the host star as a planet transits in front of it in relation to the Earth.

Illustration of transit method / Image courtesy of NASA Ames Research Center

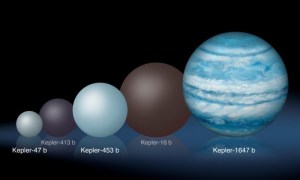

Planets that orbit two stars are known as circumbinary planets and astronomers have already confirmed several of them in our galaxy. All of the other known circumbinary planets are smaller than Kepler-1647b.

Illustration of several circumbinary planets discovered compared to Kepler-1647b / Image courtesy of NASA

Typically, larger planets are easier to identify because they dim the light from their host star more prominently than smaller planets during transits. However, Kepler-1647b’s orbital period is so long that it transits in front of its star less frequently than other confirmed exoplanets.

At 1,107 days (just over three years), Kepler-1647b’s orbit is the longest period of any confirmed transiting exoplanet to date.

“It’s a bit curious that this biggest planet took so long to confirm, since it is easier to find big planets than small ones. But it is because its orbital period is so long.” San Diego State University astronomer Jerome Orosz, a member of the Kepler-1647b discovery team

Compared to single-star systems, Tatooine-type planets are difficult to discover and even more challenging to confirm. In fact, Kepler-1647b’s transit was originally noticed back in 2011 by SETI Institute astronomer, Laurance Doyle. It then took several years of analysis to confirm that the dip in brightness noticed in Kepler data was indeed caused by a circumbinary planet.

“But finding circumbinary planets is much harder than finding planets around single stars. The transits are not regularly spaced in time and they can vary in duration and even depth.” San Diego State University astronomer William Welsh, a member of the Kepler-1647b discovery team

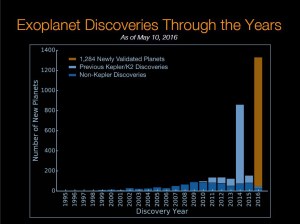

Timeline of exoplanet discovery / Chart courtesy of NASA

In the seven years since the Kepler space telescope was launched, astronomers have confirmed a couple thousand exoplanets in a single batch of sky in the Milky Way Galaxy, including a few planets very similar to Earth and Venus. Just two months ago, NASA announced the largest batch of new planets ever discovered with 1,284 confirmed exoplanets at once.

“Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy.” Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters.

Throughout modern history, scientists believed that there were other planets out there, but Kepler was the crucial tool required to prove that hypothesis. Because of data from Kepler, scientists now know that planets could be even more frequent than stars in the universe.