On Thursday a half-day conference taking place in London’s Kings College heard a range of views about the U.K.’s draft Investigatory Powers Bill, currently before parliament. The government’s intention with the IP Bill is to pass legislation that cements and extends the surveillance capabilities of domestic intelligence and law enforcement agencies to keep pace with tech developments in the 15 years or so since existing legislation was formulated.

Speakers at the event described it as a historic opportunity for the U.K. to lead the world in creating a transparent legal framework for the operation of secret state surveillance powers. However others noted the same opportunity means there is a parallel risk of badly cast legislation enshrining surveillance overreach and encouraging other countries down a similarly problematic path. The stakes, all agreed, could not be higher.

The timetable for examining what is a complex, technical and lengthy (running to some 300-pages) piece of legislation is relatively short, given the government wants to whole process to be done and dusted — with an act in place — by the end of the year when a sunset clause means existing emergency surveillance legislation, DRIPA, will expire.

The government has already been accused of trying to undermine the work of the joint select committee, currently examining the IP bill, by not giving it enough time to do a proper job. So there is also a very real risk of inadequate scrutiny of complex proposals with opaque implications resulting in major collateral damage to citizens’ privacy and security. And potentially also to the competitiveness of U.K.-based Internet companies, if businesses end up losing the trust of users because of ill-thought-through legal requirements foisted on them by politicians.

One plainly worded intervention came from Apple last month, with the company warning in a statement submitted to the bill committee that: “The bill threatens to hurt law-abiding citizens in its effort to combat the few bad actors who have a variety of ways to carry out their attacks. The creation of backdoors and intercept capabilities would weaken the protections built into Apple products and endanger all our customers. A key left under the doormat would not just be there for the good guys. The bad guys would find it too.”

Another Snooper’s Charter?

The IP bill was introduced to the U.K. parliament by Home Secretary Theresa May in November. As well as the joint select committee, due to report in mid-February, a bill committee will also examine it, line by line. And it will be put through Parliament and House of Lords scrutiny in the coming months, allowing for MPs and Peers to debate its measures and propose and vote on amendments — before any vote on a final bill, incorporating any agreed amendments, can take place.

Assuming, of course, the legislation is not derailed by majority opposition during the scrutiny process. The Conservative government’s prior attempt to legislate in this area — the 2012 Communications Data Bill (CDB) — had to be withdrawn when the government’s then coalition partner, the Liberal Democracts, refused to support it, dubbing it a ‘Snooper’s Charter’.

The new IP Bill has also been branded a Snooper’s Charter by critics, not least because it includes an expansion of surveillance powers — such as a requirement that ISPs log and store details of the websites users have visited for a full 12 months. It also sanctions bulk equipment interference — aka the mass hacking of devices — as an investigatory tool. And has some worrying wording around encryption, hence Apple’s concerns.

More broadly, the bill seeks to give explicit legal blessing to mass surveillance, at a point when the U.S. has been making moves in the opposite direction, reviewing and rolling back so-called ‘bulk collection’ initiatives, via the likes of the USA Freedom Act. At the same time, UN and European rights bodies, including the European Court of Justice, have censured mass surveillance on human rights grounds — calling it a threat to democracy.

In the U.K., it’s been the opposite story since the the 2013 Snowden revelations, with continued government attempts to shore up, rather than roll back, mass surveillance — culminating in the current bid to enshrine the practice at the core of the surveillance state by giving it a legal footing, balanced — argue supporters — by robust oversight safeguards. Safeguards that critics of the bill counter are not nearly robust enough.

Security is one core critical theme, with concerns, for instance, about the vast honeypot of user data the bill proposes to create, via provisions such as the aforementioned ‘Internet Connection Records’, risking becoming an inevitable target for hackers or blackmailers. And concerns about government agencies working to intentionally exploit and enlarge vulnerabilities in software and systems. So the U.K. government stands accused of, on the one hand, claiming it’s increasing investment in cyber security, while at the same time trying to hand a mandate to another set of government-funded actors to undermine digital security at will.

The opposition view

The Conservatives are a majority government so don’t need a junior political partner to sign up to their legislative plans to get bills through Parliament, meaning the IP bill looks likely to face less opposition than the failed CDB. And it’s not at all clear that the official opposition Labour party has any philosophical objections to increasing the capabilities of the surveillance state. Or to the practice of mass surveillance, specifically.

Shadow Home Secretary Andy Burnham welcomed the bill when it was introduced in November, couching it as neither a Snooper’s Charter nor mass surveillance — although he subsequently wrote to the Home Secretary saying the party wanted to see stronger safeguards put in place in the legislation, especially around the issue of judicial sign off for authorizing interception warrants.

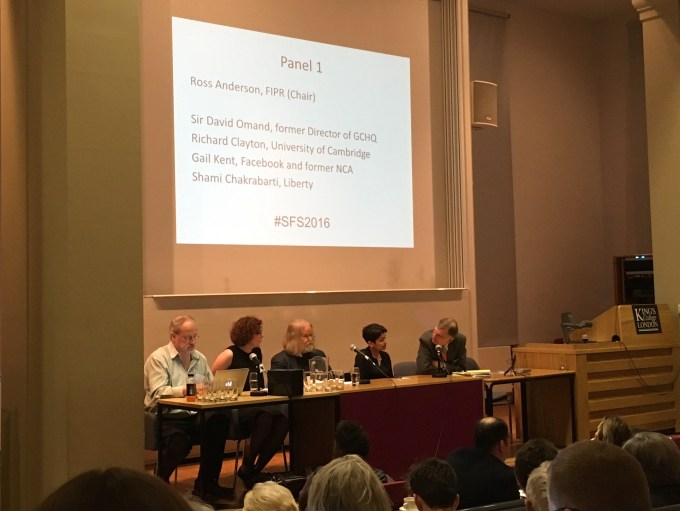

Speaking at the Foundation for Information Policy Research‘s Scrambling for Safety 2016 event on Thursday, Labour MP Keir Starmer, who noted he would be the party’s lead on the IP bill, said it’s clear new legislation is needed to govern surveillance powers, given that the outdated and often obscure patchwork of existing legislation currently used to authorize surveillance activity is long past its sell by date.

Just as powers are extended so must safeguards be.

He also said he supports expanding state surveillance capabilities — but also with a caveat on safeguards. “There is a requirement for extended powers,” said Starmer. “But just as powers are extended so must safeguards be — and this must be the absolute governing principle, I think — from the Labour party point of view, from any point of view… The safeguards have to be more robust, more transparent than they were before.”

He went on to argue that the so-called ‘double lock’ sign off mechanism for intercept warrants proposed in the bill, which would mean the Home Secretary retains the power to sign off intercept warrants but a judge must also sign off the same warrant (although there is also a provision allowing warrants to be signed off by the minister in ’emergencies’ and retroactively looked at by a judge), would only be appropriate if judges “play a real part”, rather than what he described as the “long arm judicial review” currently proposed.

“I do think that if judges are to play a part they’ve got to play a real part,” he said. “And therefore an exercise which is in truth a rubberstamp is not worth having. Close up scrutiny — looking at the material kind of our use of these intrusive powers — is a different proposition.”

Data protection and data retention provisions in the bill will also require greater scrutiny, Starmer added.

But the former director of public prosecutions also took time to flag up what he couched as the “vital” role played by communications data when it comes to investigating and prosecuting “serious and difficult cases” — giving the example of the thwarted 2006 plot to simultaneously bring down multiple airplanes mid way over the Atlantic.

“There was a very elaborate plot… that was uncovered in real time in a number of places, including in North London. And there was a real scramble to get the data available very quickly because once it became clear there was a plot it was very important to move from that stage to stopping any part of that plot being implemented,” he said.

“In very many cases we would not have been able to prosecute without the sort of data that was made available because of the existing [surveillance] regime,” he added, thereby giving tacit support to so-called ‘bulk collection’.

Call for a more targeted approach

Speaking during another panel, Shami Chakrabarti, director of U.K. civil rights advocacy organization Liberty, argued that the current application of surveillance capabilities in the U.K. has in fact yet to be justified — arguing that far more debate needs to take place about targeting.

“Just because things were happening outside the law and it is now proposed to put them inside the law doesn’t mean that we’ve got the balance right,” she said, adding that targeted surveillance has been the “traditional approach” in open, democratic societies, rather than the mass surveillance measures set to be enshrined in law if the bill passes in its current form.

It’s notable that the IPT, the oversight court for the U.K.’s intelligence agencies, last year ruled against GCHQ for the time in its fifteen year history (and did so on more than one occasion), deciding, in one ruling, that the agency had acted unlawfully in its data sharing activities with the NSA. Yet despite such rulings, the U.K. political establishment appears almost entirely comfortable with — and ready to legislate for — mass surveillance.

“I completely applaud and support the idea we must now come out of the shadows when setting the legal framework that will then be applied, of course, often in the shadows but we still must have a debate,” argued Chakrabarti. “Just because things were happening without public knowledge or parliamentary insight, let alone judicial sign off, doesn’t mean that the balance is yet correct — that we have proportionality [when it comes to state use of mass surveillance].”

She went on to argue that “proportionality principles”, as applied under the European Convention of Human Rights, have generally required “a more targeted approach to surveillance than you see in many parts of this bill”.

“That is a real challenge,” she added, emphasizing it’s her view that “an operational case for using mass surveillance has still yet to be proven”.

The risks of overreach

Various specific concerns about the proposed legislation were also aired on Thursday with speakers from a range of NGOs, and legal and industry bodies, as well as politicians, discussing the draft bill in three themed panel sessions, with questions taken from the audience.

Panelists were, for instance, asked how police or intelligence agencies would be able to assess the risks of hacking a particular piece of equipment — sanctioned by the IP bill under its ‘equipment interference’ and ‘bulk equipment interference’ (aka: mass hacking) provisions — given the complex interplay of digital devices and services already evident in a nascent but growing Internet of Things.

Might there not be huge potential risks, even potentially risks to life, of interfering with digital services, asked one audience member — and how could an untargeted process such as mass hacking avoid generating unknown ‘collateral damage’, let alone be judged ‘proportionate’ by those authorizing such activity?

[If] you don’t know who is actually going to be subject to this type of interference, then how can you possibly judge proportionality?

“On the question of how do you assess the risks of interfering with a technology, if you’re going to do at all it needs to be extremely targeted,” argued Caroline Wilson Palow, of civil rights advocacy organisation Privacy International. “Otherwise you can’t judge proportionality — you don’t know what device you’re targeting, you don’t know who is actually going to be subject to this type of interference, then how can you possibly judge proportionality?”

“This problem we have with the powers across the bill, not only with equipment interference,” she added.

Another speaker at the event, Malcolm Hutty of Internet infrastructure membership organization Linx, also raised concerns about the risks of state actors causing unknown damage via legalized hacking activity.

“If you were to hack into a DSLAM or something like that, you might think that that’s only supplying broadband service for a relatively small area — it can’t be that significant can it? But in fact how do you know whether that it providing, amongst other things, the back up line for some safety critical service, maybe a water purification system or a monitoring system for somebody’s health.

“The idea that an intelligence officer can assess what the likely impact would be if that vulnerability that they exploit and maybe exacerbate — that they could assess the impact of that without knowing… not only what that system is and how it works but how it was used seems to me to be deeply problematic.”

The consequences of a mis-assessment… range from the minor to the wholly catastrophic.

“The consequences of a mis-assessment of that range from the minor to the wholly catastrophic,” he added. “It’s our view that this particular part of the bill needs to be made much tighter, not in the interests of the balance between privacy and security, but to avoid doing significant harm to the security of the U.K.”

Anthony Walker of trade association TechUK, warned of the potential economic impact of companies losing the trust of users as a result of being subject to explicitly broad state surveillance powers.

“This question around equipment interference has some real direct relevance in terms of the extent to which companies are subjected to these kind of broad powers can potentially sell their services around the world. And that can be trusted by their customers around the world. I think that’s a really significant commercial and economic impact that we need to bear in mind,” he said.

He also argued that many aspects of the bill, including specifically the language around encryption, is too vague — and is therefore open “to interpretation”. (A point also made to the joint select committee last month.)

“There is definitely more work to be done to improve the transparency of the bill. What are these powers? What do they actually mean? And in many ways I think companies are struggling to really understand and fully understand the implications of the bill because there are too many aspects of the bill that they just simply don’t know what it means,” he said.

Walker also warned of the risks of the U.K. being out of step with other countries’ approach to surveillance legislation, arguing that being an outlier might well be counterproductive by jeopardizing the international co-operations needed for data to flow across borders.

“The more that we insert extraterritorial powers into the bill the more that we go against some of the norms that are emerging elsewhere, the harder that international co-operation becomes. So the extraterritorial issue is, I think, very important because it potentially undermines the security objectives we’re all trying to achieve,” he said.

“Technology is global, the threats that we face today are global, the axis are global, companies are global. If the security services are going to be able to access the information they need at the time that they need it that depends upon international co-operation between agencies, between companies,” he added.