Remember Danger? The mobile maker Microsoft acquired for $500 million back in 2008 in the hopes of firing up its mobile fortunes? Things didn’t pan out quite so well for Microsoft of course, but Danger co-founder Joe Britt is doing just fine. In fact he’s uncloaking his new startup today — one he’s presumably been ploughing some of his unspent Danger money into.

“We’re very well funded,” Britt tells TechCrunch, discussing his new project, an Internet of Things platform play called Afero, but declining to say exactly how well funded, nor who his investors are (he will say his prior employer, Google, is not one of them).

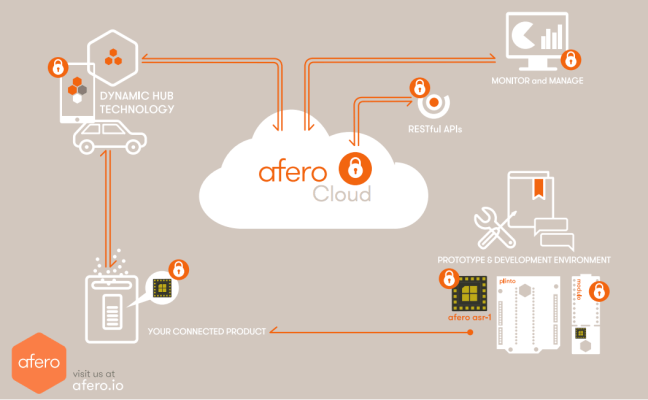

The team, currently numbering 42 people, has been building Afero in stealth since April 2014, filing some 50 patents along the way. It’s launching the product and cloud service today, selling a Bluetooth Low Energy connectivity module for IoT (including a developer board); an SDK and developer tools; and a cloud platform plus RESTful APIs to tie everything together.

The basic idea is that Afero aims to take away the headache of figuring out the connectivity layer for IoT devs so developers can instead focus on whatever the core functionality of their smart device is — whether they’re building something relatively simple, like a smart lock, or a more sophisticated IoT device like a connected home appliance or even a car.

“We’re able to help them by providing this secure connectivity and easy way to interact with their devices without them having to become subject matter experts on a lot of things that may not be relevant to what they really want to do,” says Britt. “Fundamentally it lets our developers focus on the differentiating aspects of their products, rather than focus on this necessity of connectivity that is inherently extremely complex.”

Britt originally moved to Silicon Valley in the earlier ’90s to work for Apple and was most recently clocking time at Google on Android projects with Danger (and Android) co-founder, Andy Rubin. So he’s already had a long and lucrative tech career. But that’s not stopping him from dreaming bigger. “If you look back at my career it’s always been about these kinds of comprehensive devices that have a hardware component and connect up to the cloud,” he adds.

In potential scope at least, Afero could be bigger than Android — given analyst projections about the potential size of the IoT devices market (Gartner forecasts more than 20 billion connected devices by 2020), and the fact Afero is hardware and software agnostic. Its pure play platform philosophy is to integrate with whatever other software or even hardware platforms (Arduino etc) devs want to work with on the rest of their project, but with Afero taking care of the connectivity piece.

“The developer can choose whatever hardware, operating system, development tools are most appropriate for the problem they’re trying to solve, or the product they’re trying to build. And then they can augment that product with the Afero module, the SR1, to give it the connectivity that enables it to be a secure connected device,” says Britt.

“This is one of the challenges. For trying to develop a system for giving connectivity to this broad range of [IoT] products without asking the developer to radically change the way that they are building whatever it is that they are building,” he adds.

The other big push here is on the security side. Britt touts best in class security being baked in to Afero. And while he won’t say it’s ‘hack proof’ he does stress that the security system is “hermetically sealed” — so this is about reducing risks and using ‘best in class’ practices. And that’s welcome given how much of a wild west the nascent IoT space can be on this front.

(NB: Security is not the same as privacy in this instance, so if you’re concerned about third party entities accessing data from your smart devices after it’s taken into the cloud for processing that’s a whole other set of considerations. Afero’s security pitch is about locking down IoT device chatter from hackers.)

“We have an asymmetric key system, very similar to what you use with your computer. It has a tiered key structure, where there’s a root key and other keys descend from that. The devices and the service negotiate session keys that have programmable lifetimes. And then in addition to the pure sort of encryption approach, we’ve also built a number of counter measures into the system to make it difficult to characterize traffic patterns — because that’s another vector of attack,” says Britt

“The core of one of the problems with the other IoT connectivity solutions that we’ve seen… is that when you ask the developer to do the kind of deep integration that other IoT platforms require you’re inherently opening up the possibility for either intentional or accidental modification of something in a way that compromises security.

“The way that Afero was designed, through this module, the security system is hermetically sealed from the device all the way up to the cloud. And so from the developer’s point of view it’s very simple — I connect this module to my product and I enjoy all of this higher level functionality — and at the same time I don’t have the hazard of inadvertently modifying something that’s going to compromise the security,” he adds.

Afero has hardware partnerships, including with Qualcomm and Murata, for its connectivity module. On the customer front, it has signed up companies including healthcare IT systems provider Infocom and toys and video gamers maker Bandai to use its platform to power the connectivity of their connected devices going forward.

Britts reckons the “sweet spot” in terms of target customers will be small and medium enterprises, but there will be scope for “hobbyist developers” to use it too. The business model will include a freemium option for those guys, with pricing scaling to various SaaS tiers to accommodate larger entities. The technology itself is built to be scalable from individuals to enterprises.

“Fundamentally Afero is a services company,” he says. “For development and experimentation you can pick up one of the development boards, download the software and use it for free. And build prototypes and experiment with it. And then for commercialization of your product then we have different tiers of service model.”

“If you look at the other development systems for adding connectivity that are out there usually there’s multiple pieces including fairly substantial components that have to be integrated into the design,” adds Britt, holding up the Afero radio module, which is less than 1cm square, and includes multiple IO lines that can be configured in different ways to enable the developer to control and/or monitor their device.

“We have a developer tool that we provide that lets you specify how the module is being embedded in your product, what those IO lines are doing,” he notes. “You’re able to specify how you’re using the product in your design and then the tool automatically generates a number of things for you — it generates configuration data, that goes into the module, for setting it up for your application; it generates a template for the UI, for a mobile application; and it generates a set of RESTful APIs for the cloud, so that you can access it from there. And then all those pieces are deployed from the tool, through the Internet, to each of those different places. And then once that’s done you have a completely connected device.

“So the development process goes from having to understand and learn about a lot of new technology to integrate into your product to sort of picking that off the table and letting you focus on whatever aspects of your product are most important in differentiating.”

There are startups targeting consumer smart home security with a hub device and cloud processing promising to lock down multiple smart devices in your home. And there are also developer-focused startups offering tools, kits and cloud platforms promising to help IoT makers get started prototyping, such as relayr, which look more similar to Afero. But Britt claims his approach is unrivaled in scope and scale at this point.

Why is no one else doing this, as he claims. He argues that’s down to “volatility” in the IoT space, and companies thinking of the connectivity problem in the “classical way” — i.e. gathering together disparate parts themselves, rather than a pure platform play. “They’re doing that because there hasn’t been another model available. If you think about what accelerated the creation of the web it was tools that made it fast and easy to publish data. And it augmented or extended the existing best practices of the people who were using that as a tool,” he says.

“The other thing that was critical for the development of the web was that it had to be secure. And so sort of distilling everything down to those component parts, and doing it in a way that can co-exist easily with all of these different kinds of embedded systems — it’s fundamentally a hard problem.

“The team has been working on this for almost two years now. We’ve also had the benefit of being able to cloister ourselves, and think about what are the appropriate solutions to these problems. And at the same time interact with our founding partners [e.g. Qualcomm] to make sure that the technology that we’re building really did in fact solve these problems.”

Afero is hosting its cloud services in six data centers at this point — two on the East Coast U.S., two on the West Coast, and two in Japan. That cloud model means there are inevitably questions about data transport from regions like Europe, should Afero secure customers who are selling devices in the region thanks to the current limbo left by the invalidation of the EU-U.S. Safe Harbor data transport agreement. The ECJ decision that struck down that agreement was itself triggered by wider legal concerns about U.S. government surveillance programs’ easy access to cloud data. That issue isn’t going to go away — however little it’s on Afero’s radar right now.

“At this point we don’t have a customer that is requesting segregated data. Technically there is no problem with spinning up another data center, or data centers in Europe — and imposing different policies for how the data is segregated,” says Britt, when asked about this point. “I think that’s an example of why it’s better to have these very high level controls, rather than trying to push it down to lower levels where you’re just talking about more disparate devices. And so a greater challenge to understand what potential hazards exist within them.”