After Uber and Lyft emerged to fundamentally challenge taxis and change on-demand transit, a wave of bus startups has cropped up to address group and scheduled transportation.

Chariot, a bootstrapped San Francisco-based startup that got off the ground earlier this year with a line from the Marina to downtown, is taking a slightly novel approach to generating ideas for new routes. They’re crowdfunding new lines.

What’s on deck?

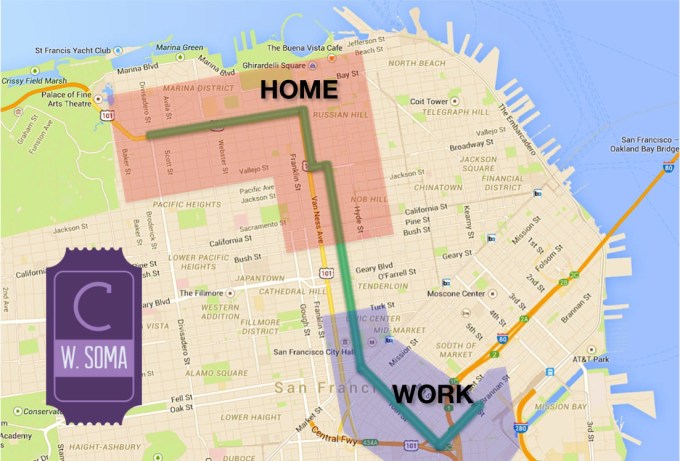

A line from the Marina, Cow Hollow and Russian Hill to what it calls Western SOMA. If 120 riders pre-commit to the idea of this route and buy monthly passes upfront, the campaign will tilt and Chariot will launch the route.

“We think this is a great way to take the risk off our table and get the community involved in putting together better commuting options for themselves,” said CEO Ali Vahabzadeh. The discounted monthly passes for the proposed route range from $96.75 to $116.10, which is lower than the typical $129 they would plan to charge.

With Chariot’s existing two routes, the company is doing about 2,000 rides per week and has provided roughly 35,000 paid rides to date. Prices generally run about $4 a ride, but they can dip lower if consumers go for a full monthly pass. The company also just launched a mobile app last week that will let people check in to their rides or check to see where buses are in real-time.

While it is definitely a politically sensitive time to be launching anything in San Francisco around buses, given the Google bus blockades from the last year, there is historical precedent in the city for a mix of both public and private solutions to transit.

Many of the city’s older MUNI streetcar lines were originally created by private entrepreneurs in the late 1800s or early 20th century, then were later purchased and absorbed into MUNI after the emergence of the private automobile challenged their financial viability. Then, private jitney services coursed through the city for about 60 years, covering inter-city transit gaps that were later addressed by the regional BART system.

Crowdfunding routes is an interesting strategy toward quickly generating profitable new routes, compared to the complex science and art of transit planning. The city’s process of adding or removing bus stops is a very lengthy, deliberative and often politically contentious one. Bus rapid transit routes, or BRT, for short would help speed MUNI buses through the city at a faster pace with specially designed stops and lanes. They have been explored for more than a decade in San Francisco, but they won’t be up and running until 2018 even though they’re tried and true in Latin American cities like Bogota and Mexico City. There’s just a lot of opposition from drivers who want to preserve parking spots and traffic lanes.

Then, while MUNI has stops every few blocks that slow lines in aggregate, it’s politically difficult to reconsider any of them. Every stop has its own constituency and there are concerns that it would be difficult to make elderly or disabled residents walk the extra distance. The city has been working on a transit effectiveness project for six years that painstakingly collected data on where people get on and off MUNI, cost millions of dollars and made a series of recommendations that still have yet to be seen through. (If you want to read an epic explanatory piece about MUNI’s various issues, this piece by Joe Eskenazi is it.)

Some critics have raised worries that these bus startups, like Chariot and competitor Leap Transit, will cause the broader public to disinvest in the city’s municipal transit system. (Back in the 1970s, the city actually stopped issuing jitney licenses and voters backed a ballot initiative protecting MUNI on this very concern.)

Vahabzadeh said, “I would say actually we’re taking a lot of the overflow. A lot of our customers are actually waiting three or four buses which are overcrowded. I think we’re actually bringing more commuters back into the transit-first fold as opposed to having them drive to work and congest the streets even more, or commute through Uber, Lyft or Sidecar.”

He pointed out that Chariot’s daily ridership is a fraction of of a percent what MUNI does on a daily basis with north of 700,000 commuters per day last year.

“We’ve got a long ways to go before that debate makes sense,” he said. (To be fair though, Chariot’s crowdfunding campaign does specifically call out the competing MUNI 47 and 49 lines for being too slow.)

For the moment, it appears that San Francisco voters are actually very supportive of mass transit. They overwhelmingly approved a $500 million bond for public transit last week with 71.3 percent of the vote. It’s the first bond supporting MUNI that the city’s been able to pass since 1947. Voters simultaneously shot down a car-centric proposal backed by Sean Parker that would have preserved free parking.

Furthermore, once BRT launches in the next few years, these city lines have dedicated lanes that other vehicles, including these private shuttles, shouldn’t be able to legally use if enforced. It could be an interesting mix.