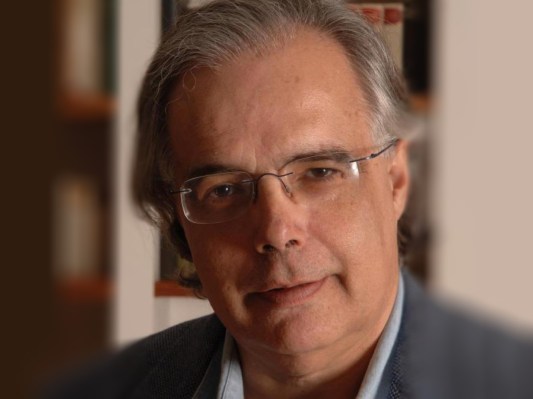

Two decades after he served as the chief negotiator for peace talks between the then Yasser Arafat-led Palestine Liberation Organization and Israel under Yitzhak Rabin, Uri Savir remains ever optimistic.

Although the Oslo Accords laid tentative groundwork for an eventual two-state solution, it was never realized. Once again, the region is only just recovering from another conflict between the Hamas-led Gaza Strip and Israel.

But Savir is still at work on Israeli-Palestinian peace decades later, this time through a digital diplomacy-style effort called YALA, which leverages Facebook and other platforms to promote online discussions between Arabs and Israelis. It has roughly a half-million followers on Facebook spread throughout many Arab countries and Israel. It bolsters that by following through with more in-depth online modules on citizen journalism and online conferences in economic cooperation and peace-making.

He said a mistake he made two decades ago was in assuming that elite-led peace talks would be broadly accepted by both Palestinians and Israelis.

“For the first time, we have an opportunity to create what could be known in international relations as ‘participatory peace,'” he said. “In other words, this would be a peace in which the societies would be involved. Peace imposed by leaders is not sustainable. Social networks allow people to ask themselves if they want peace, and how they want it. We could have dialogues between thousands of people, rather than a few elites.”

His movement, which picked up momentum around the beginning of the Arab Spring three years ago, comes at a critical and fascinating time for online diplomacy in the Middle East.

Right now, there is this ongoing, very complex propaganda battle that is taking place through YouTube and Twitter between groups that have a more militant interpretation of Islam and others that are tolerant and staunchly against the use of terrorism. There are some pretty fascinating stories on how ISIS, or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, which has captured large swaths of territory in Northern Syria and Iraq, uses social media and even builds Android apps to recruit foreign fighters. At the same time, there are online Muslim-led movements from the U.K. and Western Europe that are actively denouncing ISIS’ interpretation of Islam through hashtag campaigns like #NotInMyName and through YouTube videos from British imams.

Even the State Department is fighting back online through its own social media campaign, under the hashtag #ThinkAgainTurnAway. YALA is part of the Peres Center for Peace and is also partially financially supported by the U.S. State Department.

“The Palestinian-Israeli peace process started 20 years ago, and it may take another 20 years. But in the meantime, we have to get peace assets just like terrorists are accruing conflictual assets,” Savir said. “This is a struggle between two parts of society. By and large, it is between secularists who have an inclination for freedom and technology and religious fundamentalists, who have an inclination for oppression and backwardness. That is the struggle that’s going on.”

All in all, it shows that even as tech industry leaders like Mark Zuckerberg tout the benefits of making the world more “open and connected,” social networking platforms are just tools that can be used for both peace and war. There was an initial wave of hope and euphoria that ushered in the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Egypt and other countries, but it has since given way to anarchy in Libya, ISIS in Syria and Iraq and a new military strongman in Egypt with recently elected President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. The problems of building inclusive and responsive governments and civil society is just a lot more difficult than any Twitter or Facebook-facilitated youth demonstrations can solve in a matter of mere years.

ISIS, in particular, has proven incredibly adept at using Twitter, YouTube and Facebook to show what life is like in its capital of Raqqa, Syria even in spite of quick takedowns. Their relationship with the Western press has been totally altered by the existence of direct channels through social media. Journalist friends of mine who were based out of Gaza during the height of the conflict this summer said that Hamas, which looks moderate when compared to extreme ISIS, was generally tolerant of Western reporters. It needed third-party journalists to tell visceral stories about the poor living and economic conditions in the Gaza Strip amid an Israeli blockade, and humanize the loss of 2,000 lives even as it also fired rockets into Israeli towns and cities. But ISIS doesn’t even really need reporters in a classic sense, because it can speak to its audience directly. It has instead beheaded them and even perversely used journalists taken hostage like John Cantlie to spread its propaganda. Because of the sheer security risks, the only Western outlet to get any kind of meaningful look into life in Raqqa has been Vice News with a five-part series from documentary filmmaker Medyan Dairieh.

“Technology is neutral,” Savir said. “It can be used for either positive or negative values. But we are the positive answer to ISIS.”

Savir is trying to make YALA more than a Facebook like or online slacktivism. On top of the Facebook following, they started building online academic courses through Coursera to build up leaders in other parts of North Africa and the Middle East and train members in citizen journalism. In the latter, they were able to instruct nearly 1,000 students on how to write blog posts and articles around peace-making.

He still envisions a two-state solution based on 1967 borders, with a shared capital in Jerusalem, no right of return and security arrangements with international participation that don’t infringe on Palestinian sovereignty. (All of these ideas are, of course, still vociferously debated in both Palestinian and Israeli politics.)

He has been both critical of Israel’s settlement policies, and has said he favors strengthening the more moderate Fatah government in the West Bank over Hamas. Both Fatah and Hamas just agreed last week to give the Palestinian Authority more power in the Gaza Strip in order to secure billions of dollars in aid for reconstruction.

“We live amid a shaky co-existence and it will still take a lot of suffering,” Savir said. “Oslo began the track that will make a two-state solution inevitable. But we need to develop leaders in a younger generation and I’m totally optimistic.”