It’s scary to move a billion people’s furniture. That’s why Product Manager Michael Reckhow tells me Facebook built Paper. This fear has spawned the standalone app boom of 2014. Tech giants are experimenting with new user experiences outside the hallowed halls of their main apps that are too important to meddle with.

But while the press and public scrutinize the success of these different apps like Facebook Slingshot, Instagram Bolt, and Dropbox Carousel, they may be missing the point. Standalone apps are supposed to fail, at least most of the time.

They’re like a free play in football. The referee has thrown the flag but will let the action continue. The team will get a do-over if they want it. In the meantime, they can try something risky without the consequences, but reap the benefits if things go right.

The Risky Redesign

A common adage is that 1 in 10 startups succeed, but even fewer are true home runs. In consumer social apps, the odds can be even worse. Not only do you need a fun, compelling, immediately accessible product, but you have to foster a loyal community around it.

Constructing that inside another app without screwing up the original experience or burying the new one is nearly impossible. The big guys stopped trying a long time ago. At first glance, Facebook and Twitter haven’t changed in years. Navigation schemes have gotten quicker and images have gotten bigger, but they both fundamentally look and feel the same as they did in 2010.

Redesigning core features can be precarious. One false move can drive away millions of users, along with the dollars they generate. Burying powerful features in a main app relegates them “second-class” experiences, as Mark Zuckerberg told me in an on-stage interview last year. And few features are important enough to unbundle into companion apps.

Redesigning core features can be precarious. One false move can drive away millions of users, along with the dollars they generate. Burying powerful features in a main app relegates them “second-class” experiences, as Mark Zuckerberg told me in an on-stage interview last year. And few features are important enough to unbundle into companion apps.

Facebook Messenger has turned our propensity to chat on mobile into a 200-million-user phenomenon that’s now going from optional to the only way to send Facebook Messages on mobile. But Facebook users have mostly yawned at the high-design of Paper and are sticking with the traditional News Feed.

When giants do overhaul features or add new ones, they’re stuck so far off the beaten feed that they’re forgotten or overlooked by many. Twitter’s tinkering with Discover, or Facebook’s Nearby Friends and Nearby Places get a fraction of the following as their fellow features with the spotlight. If they do gain traction, it’s among isolated clusters or a special demographic. Instagram Direct has 45 million monthly “active” users out of the app’s 200-million-plus total, but that’s just people who at least open a Direct message. The number who actually send them is surely much smaller.

The Expensive Acquisition

While building these new apps within ones that are already exist is tough, not building them can be extremely costly.

Facebook was the biggest photo-sharing app in the world, but it wasn’t built for mobile. Instagram combined filters with a Facebook-style feed that ditched everything but photos, and it took off. Facebook would have to spend $1 billion to buy the upstart before it caused serious problems. Since, Instagram has grown from around 30 million users to over 200 million. Had Facebook hesitated, it would have had to pay much more for it later, or worse, see the app fall into the hands of a competitor.

It wasn’t Facebook or Twitter or Google that discovered the power of ephemeral messaging. It was Snapchat, which had no previous product to shoehorn its self-destructing photos into. It took Facebook a year to wise up, and the shallow clone Poke it devised in just 12 days flopped. Sure it allowed texting, which Snapchat would eventually add. But otherwise Poke was nothing special, and Snapchat was already ordained as cool among kids.

Facebook would reportedly go on to try to buy the app for $3 billion, but get rejected. Now Snapchat is said to be raising money at $10 billion valuation. Facebook was so busy building Timeline to permanently record our lives, it wasn’t experimenting with the idea that not every photo has to live forever.

So, Why Not?

Once it’s clear that it’s hard to hatch new behavior patterns in existing apps but can be expensive to buy new apps that prove users want these experiences, the strategy of building standalone apps comes into focus:

- Cheap: Throwing a few designers, engineers, and product managers at an idea is relatively inexpensive for tech giants.

- Fast: Since they don’t have to figure out where the product fits in an existing app and can explore new styles, development is quick.

- Low-Risk: Built outside their main apps, tech giants don’t have to worry about shocking, alienating, or confusing existing users with changes.

So, why not?

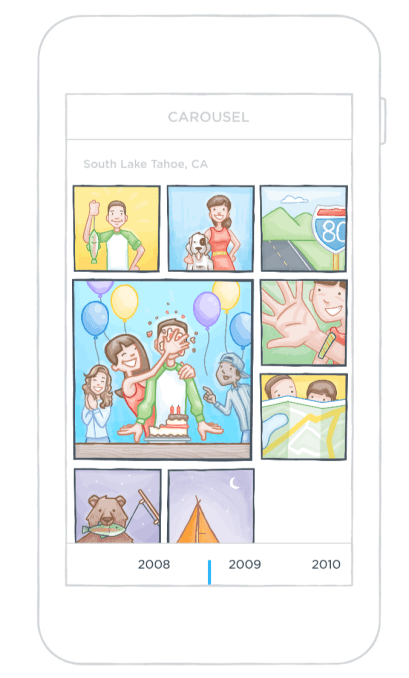

Best-case scenario, the app’s a hit, and a tech giant adds another popular product to its quiver. The app can serve as an extension of the parent company’s main brand that drives lock-in for its family of apps. For example, Dropbox’s standalone photo backup app Carousel was in part designed to get people to buy more Dropbox storage space. Or the standalone can be operated and monetized independently like Instagram with help on business, hiring, engineering, internationalization, and more from the parent company behind the scenes

Even if the app is only a middling success, it can collect data and understanding about users to be applied to a company’s main product. For example, Facebook’s first standalone photo app Facebook Camera served as a testing ground for new features for the main Facebook app. Here Facebook discovered that its little guinea pigs like multi-shot uploads and filters, so even though Facebook Camera would eventually be shut down, it developed and refined critical features through the standalone app model.

Failure Is An Option

Worst-case scenario, the app is a total flop. But how bad is that really? Some good talent was diverted from important projects, but these companies have money to hire plenty of great designers, engineers and product managers. The parent company may have delayed work on including the standalone app’s use cases into its main product, but these tech giants are big enough to have plenty of teams, and they should be working in parallel to hedge their bets. This is why Facebook started its Creative Labs initiative to foster small teams building new apps outside its core experience.

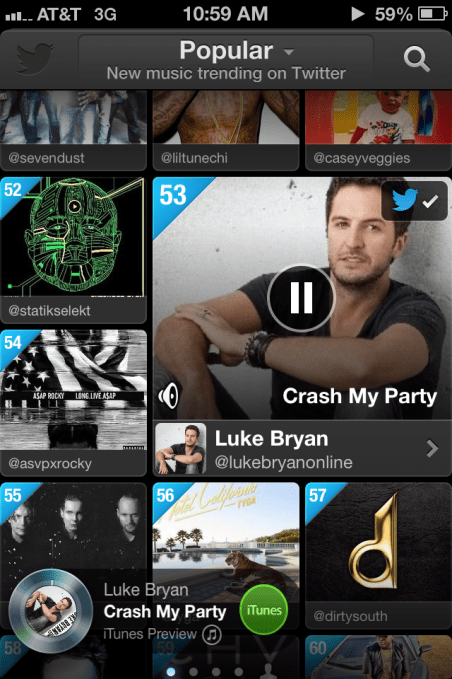

The few people who had a crummy experience with the standalone app may lose some confidence in the parent company. If the app gets shut down, those still using it might be a bit miffed. But mostly forgetting about using Facebook’s standalone feed-reading app Paper or neglecting Twitter #Music hasn’t made me any less likely to use Facebook or Twitter’s main apps. That’s the whole point of it being “standalone.” Like a captured secret agent, the parent company can disavow the failed standalone app and move forward with its main app.

The few people who had a crummy experience with the standalone app may lose some confidence in the parent company. If the app gets shut down, those still using it might be a bit miffed. But mostly forgetting about using Facebook’s standalone feed-reading app Paper or neglecting Twitter #Music hasn’t made me any less likely to use Facebook or Twitter’s main apps. That’s the whole point of it being “standalone.” Like a captured secret agent, the parent company can disavow the failed standalone app and move forward with its main app.

In the end, one of the more daunting aspects of building standalones may be the bashing a company gets from the press if an app fails. I, for one, take responsibility. There’s something snarkily joyful about watching successful companies worth tens or hundreds of billions of dollars fail at something. Facebook’s share price has nearly tripled since December 2012 when Poke launched, but the blue Snapchat clone is still the butt of countless jokes in the tech blogs and Silicon Valley scene.

Yet maybe we journalists and pundits are missing the point. Standalone apps are designed to fail, at least most of the time. When there’s massive upside, and little downside, standalone apps can be a smart investment even if they have a low success rate.

Here’s a look at the recent crop of standalones through this lens:

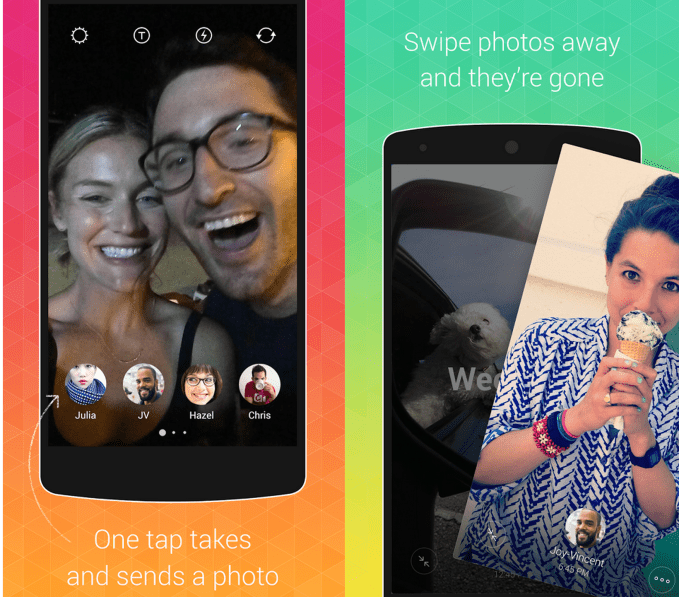

- Instagram’s Bolt is a super-fast photo and video messaging app where your friends’ faces are the shutter button. I don’t think that little extra speed is worth me using a new app. But maybe it becomes the way people photo message their closest friends and family.

- Dropbox Carousel automatically syncs all your camera roll and new mobile photos to the cloud for easing storage and saving. It’s seen slow traction, though Dropbox was on to something with the idea that lots of people cherish but don’t backup their mobile photos. But maybe it could have been a huge driver of Dropbox adoption if it blew up.

- Facebook’s Slingshot plays on curiosity, allowing you to mass-message friends with photos and videos that can only be viewed if they send you one in return. It’s still early days for Slingshot, but perhaps reply-to-unlock just introduces too much friction. But maybe the mechanic is a viral sensation, and Slingshot helps Facebook steal attention from or box out Snapchat.

- Twitter #Music lets you listen to and share the most tweeted songs, or check out jams from artists followed by your favorite celebrities. It never gained traction and was eventually shut down. But Twitter surely learned a lot about how people want to share songs. And maybe it could have made Twitter a portal for music discovery and conversation the way it is for television.

Twitter #Music is dead, Carousel has been declining steadily, many are betting against Slingshot, and Bolt may not be special enough. But that’s okay. Like I said, they’re free plays — hail mary passes after the flag. You don’t see NFL teams take flack if they go for the touchdown when there are no repercussions. So instead of harping about the low download numbers of standalone apps, maybe we should be encouraging more companies to throw for the end zone. What have they got to lose?