When it comes to getting consumers to pay for things on a subscription basis, some services fare better than others. A growing number of people seem happy to pay for entertainment-based offerings like Netflix or on-demand streaming music, for example, while “box of the month” clubs and subscription-based shopping sites have been something of a mixed bag. More recently, a handful of startups have begun working to introduce subscriptions into a new category: e-books.

At first blush, e-books seem like the next obvious choice for subscription-based commerce under the unlimited access model. It worked for Netflix with TV and movies. It’s starting to work for Spotify for music. So why not e-books, then?

NEW PLAYERS DELIVER E-BOOKS ON DEMAND

There are few key players in this space today, ranging from better-established companies to early-stage startups. All want to become this generation’s “Netflix for e-books.” Some founders pitch their companies with that very tagline. For consumers, that means you pay a small monthly fee for unlimited access to the company’s e-book collection, which varies in size depending on the service you’re using. You can then read those books on your computer, smartphone, and tablet, to the extent that the service allows.

Notable new entrants in the space include six-year old social publishing company Scribd, a younger iOS-first competitor Oyster, and soon-to-launch eReatah, which is currently in beta. While each company is angling to compete with others on feature set, publisher selection, platform support and more, they are all also competing with a much larger subscription-based player — Amazon.

Through Amazon Prime, the company’s $79 per year program, consumers receive expedited shipping, Amazon Prime Instant Video access, and, more importantly in the case of a “Netflix for e-books” market, access to the Kindle Lending Library, where they can freely borrow from over 400,000 titles with no return dates.

BETTER THAN AMAZON?

But today’s newcomers will argue that they’re doing something different from Amazon. E-books aren’t tacked on to a larger service with all of Prime’s bells and whistles, nor are they tied to Kindle devices. And for those who read more quickly, an unlimited buffet of e-books has some appeal. (Kindle owners can only borrow one library book per month.)

Explains Oyster co-founder Willem Van Lancker in a perfectly crafted pitch, “we’re so much more than a bag of books and a search bar…we’re really all about building this all-in-one books experience. We treat books as the unique form of media they are.” At his company, the belief is that there’s value that goes beyond the pure economics involved with e-book purchasing and lending. The company touts its technological and design strengths – books download quickly, you’re able to browse more visually by flipping through “big, beautiful covers,” and overall, the goal is to lower the bar for consumers who want a better experience for reading.

The team also believes there’s value in the aggregated reading data Oyster aims to collect. As with Spotify, which can surface trending tunes on its network, Oyster readers could also discover the hot new e-books because of this data – a social best sellers list, if you will.

“When you have that common library, it really changes sharing,” says Van Lancker. “That’s something that’s really unique to our product – if you look at Oyster, it’s built like a modern social network.”

Of course, that’s the same reasoning behind Amazon’s acquisition of Goodreads earlier this year: social data.

Goodreads had over 16 million readers at the time of the deal, but the technology itself feels stagnant and dated – especially on mobile, potentially giving Oyster an edge.

However, when it comes to community size, competitor Scribd has an advantage over both Oyster and Goodreads (at least pre-acquisition Goodreads, that is). Because of its history in the social publishing space, it has amassed a user base of 80 million actives, the company told TechCrunch when it first announced its move into e-book subscriptions.

The sheer size of its community attracted the interest of HarperCollins, which was also interested in the data-sharing possibilities Scribd was offering publishers. In fact, the company’s goal is to make Scribd the most publisher-friendly of the new bunch – a strategy it hopes will help pull in the big-name brands.

Finally, there’s eReatah, a soon-to-launch startup that offers various pricing tiers, based on how many books a user wants to check out per month. It also works cross-platform and is focused on providing personalized recommendations. But what really sets it apart is that users will be able to own the titles they download, making it more of a “book of the month” club, rather than a rental service. Still, given its subscription-based pricing, consumers may lump it in their minds along with the other “Netflix for e-books” competitors.

E-BOOKS ON DEMAND IS NOT A NETFLIX OR A SPOTIFY

While it’s too soon to call the market of a “Netflix for e-books” one way or the other, it’s worth pointing out that there are, in fact, a lot of differences between reading e-books and watching Netflix movies or streaming albums on Spotify.

Namely, in addition to competing with e-commerce giant Amazon, whose empire began with bookselling, these startups compete with other so-called “Netflix for e-books” outlets: (gasp!) local libraries. Sure, the technology may not be as robust or include those big, beautiful, Flipboard-like interfaces. And there might not be social networking capabilities that allow companies to collect, aggregate and sell user data. But in return, there’s the price point to consider – libraries let you freely borrow e-books. Consumers can borrow at least some selection of e-books from their local libraries, even if they often fail to offer wide selections or new releases, or force you to wait for your turn to check out the book on loan.

And when you’re looking into lending options, it’s also worth noting that select titles are available for person-to-person lending among Kindle owners, in addition to the lending options Amazon itself offers via Prime.

WHERE’S THE VALUE?

Then there’s the fact that the cost to purchase an individual e-book tends to fall in the same general ballpark as the monthly fees paid to these Netflix-like subscription services. In other words, if you’re not reading more than a book a month, or reading multiple titles at once, then you might not be getting a good deal. That’s a challenge that Netflix or Spotify doesn’t face since it’s fairly easy to watch more than one TV show or listen to more than one song.

Reading at least one book a month seems like a reasonable goal, and certainly it would be great if you read more. But real life tends to get in the way, and reading is an activity that requires more of an effort on the part of the subscriber. There are simply going to be months out of the year where the majority of regular people’s “reading” involves the consumption of online news and a little Facebook or Reddit. Or maybe the back of the shampoo bottle, while…well, you get the idea.

But maybe you’re not paying for value, but experience?

That’s also a heady bet when there’s nothing dramatically different about the way you’re consuming the content itself. Unlike with streaming music, which allowed consumers to free up hard disk drive space on ever-smaller devices by ditching permanent MP3 collections, or streaming video that plays iPads away from the living room, e-books — whether from a library, Amazon or an e-buffet — are still just words you download and read on your tablet or sometimes phone.

IF NOT CHEAPER, THEN WHY?

So if the argument is not that it’s cheaper (it’s not), or that the technological means of access is better (it’s not), then it’s about riding the wave of subscription-based commerce. And that’s still a risky bet.

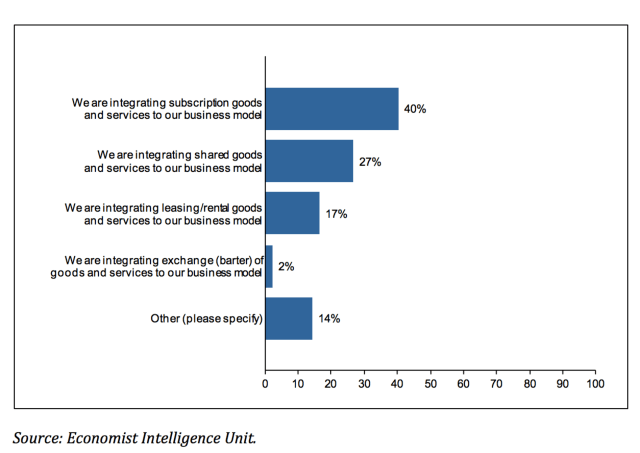

The way consumers are interacting with content for purchase is undergoing a significant shift. Eighty percent of businesses are seeing changes in how their customers prefer to access their services, according to a recent study from the Economist Intelligence Unit, which surveyed 293 business executives this summer on behalf of Zuora, a company, by way of disclosure, that serves as a backbone to many in the subscription commerce world.

Over half of the companies are currently integrating new pricing and delivering models, including subscriptions (40 percent are implementing), but also things like sharing (27 percent) and renting of goods and services (17 percent). This lends promise to the subscription model for e-books.

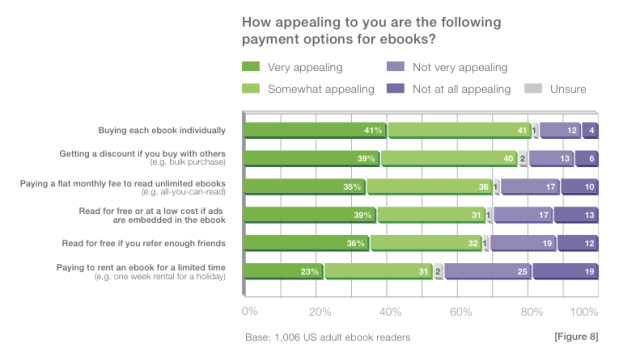

But e-commerce software company Elastic Path has done some very specific research into consumer interest in paying for e-books. And what they’ve found, explains Vice President of Marketing Matt Dion, is that while many were interested in the “Netflix-style model,” other models were appealing as well. Maybe even more appealing.

Those include buying each e-book individually (i.e. the way most people shop today) and bulk purchases. And there are more people who think a payment option, which includes embedded ads in e-books, would be “very appealing.” In fact, in terms of the most appealing idea, this ranks just below buying books one-by-one.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that the market for e-books on demand isn’t there, nor does it mean that consumer opinions won’t change. We know consumers often say one thing, then do another.

But there are formidable challenges ahead for these new e-books on demand services, including perhaps a lesser one that can’t be addressed by these charts. Among the most voracious of readers is some overlap with those who have been slow to jump on the subscription-based bandwagon in other categories. They’re the “olds” who don’t stream their music or TV on their iPad or phone. They don’t know about or use Spotify. Or, as one older but active reader who devours multiple e-books monthly explained to me when presented with the idea: “Thanks, but I don’t want to commit to $10 a month. We don’t even do Netflix.”

These startups are not for them. They’re not for the penny pinchers. And they’re not introducing a radical change in technology that eventually sells itself out of utility. It’s merely a new, and sometimes prettier, way to shop for e-books, which puts it more in line with a subscription-based e-commerce store instead. That may have appeal for those who care about aesthetics or a specific feature set, but not necessarily to a larger majority of e-book readers – and especially not those without the disposable income to overpay for their titles.

And while these companies may be taking inspiration from Netflix and its ilk, they definitely have a tougher road ahead.

Too bad. “Netflix for e-books” had such a nice ring to it, huh?