If you had any doubt that chucking in your entire life and building that iPhone case with a bottle opener you’ve always envisioned (the perfect design, honest) would be difficult, look no further than a couple recent Kickstarter failures that have been a long time in the making for proof. The Levitatr Keyboard and the Syre iPod nano Bluetooth watchband are both projects that were germinated in the heady wild west days of Kickstarter’s first beginnings, before it started to tighten the reins on hardware campaigns, and they’re both case studies in what happens if even the most well-intentioned hardware startup goes south.

Kickstarter has never claimed to be a storefront by any stretch of the imagination, so projects running into problems and failing to deliver should be familiar territory to any and all backers at this point. Anyone who has used it for any decent amount of time knows that you will get projects that just don’t materialize, and you’ll get ones that do finally ship, but that also massively under-deliver. But sometimes, you get projects where the founders are so transparent about the problems they encounter that it’s worth taking special note of what went wrong.

Levitatr Failed To Get Off The Ground

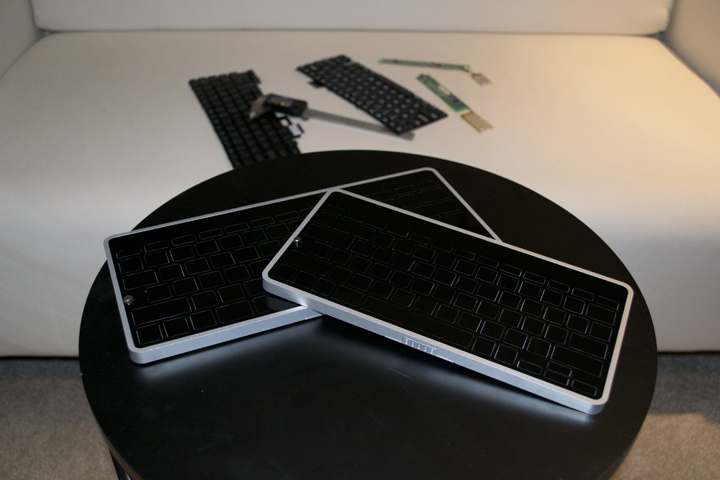

One such project is the Levitatr keyboard. Originally conceived in 2011 as an iPad and tablet keyboard accessory, this project by James Stumpf impressed with a design whereby the keys would magically appear out of slick flat surface once the accessory was powered on. Designed by Dayton, Ohio-based entrepreneur James Stumpf, it met and surpassed its $60,000 funding goal in 45 days and seemed to stand a reasonable chance of shipping by its November 2011 anticipated shelf date.

One such project is the Levitatr keyboard. Originally conceived in 2011 as an iPad and tablet keyboard accessory, this project by James Stumpf impressed with a design whereby the keys would magically appear out of slick flat surface once the accessory was powered on. Designed by Dayton, Ohio-based entrepreneur James Stumpf, it met and surpassed its $60,000 funding goal in 45 days and seemed to stand a reasonable chance of shipping by its November 2011 anticipated shelf date.

Stumpf declared Levitatr a failure via an update for backers posted to Kickstarter on August 12, 2013. He cited overly ambitious goals for the product, a shortage of funds, numerous failed licensing negotiations and his own general inexperience as the major motivating factors behind the project’s failure. The money he gathered to fund the project was all spent on attempting to build it, Stumph says, and he’s offered up an itemized list of just where it went to prove it. Stumpf also claims to have incurred considerable personal debt in the process.

Levitatr collapsed because it was more concept than concrete, with a physical prototype that promised one thing that ended up being immensely challenging from an engineering perspective to deliver. Stumpf blames a lack of willingness to compromise as part of the reason behind the project’s failure but that really engenders biting off more than one can chew: promise only what you know you’ll be able to build at project outset, in other words.

Many Kickstarter projects simply disappear into the night, but Stumpf has gone out of his way to publish a long list of supporting documents via Dropbox to support his account of how things went down, and he has been good about keeping backers up-to-date on his trials and tribulations via update. Kickstarter is designed to be a space where things can go wrong, and I think Levitatr is a perfect example of the best case scenario you could hope for in a failure, since it at least provides some guidance for others looking at building a hardware startup company.

No Crown For The Syre

Another decent example that has maybe done a bit too much apologizing and not enough explaining is the all-but-dead Syre Bluetooth watch band for the iPod nano. Right away, you see the problem; this is a project that was built for Apple’s last-generation iPod nano, the small square one that fit nicely on the average person’s wrist. The fact that it hasn’t shipped yet, well after Apple has stopped selling that device, is definitely Not Good.

Another decent example that has maybe done a bit too much apologizing and not enough explaining is the all-but-dead Syre Bluetooth watch band for the iPod nano. Right away, you see the problem; this is a project that was built for Apple’s last-generation iPod nano, the small square one that fit nicely on the average person’s wrist. The fact that it hasn’t shipped yet, well after Apple has stopped selling that device, is definitely Not Good.

The Syre was intended to solve the major oversight of the sixth generation iPod nano by adding Bluetooth to the mix via a simple, low profile dongle embedded in a watchstrap accessory. The mock-ups that the project raised funding based on showed an attractive compact device that helped the project raise nearly double its $75,000 target in August, 2012. Then, later updates to backers showed a much different device as a final engineering prototype, which was essentially a rubber nano strap case with a large, unsightly Bluetooth dongle sticking out the end – essentially, all the value of its sleek design went out the window, and backers were vocally disappointed in the change.

Syre isn’t dead technically, but it’d be fair to say the patient isn’t showing any brain activity. Project founder Anyé Spivey posted an update today that describes the project’s status and go-forward options, and both are pretty grim. Apple’s decision to change the iPod nano’s design and introduce Bluetooth to the new model had an understandably negative impact on demand both from consumers and potential distributors for the Syre: like any other 6th-gen nano-focused product, it essentially now has an extremely circumscribed potentially audience and exactly zero growth potential.

Kickstarter is meant to help get projects off the ground that wouldn’t necessarily make it to first production on their own, not to provide the funds to underpin a business in the longterm, so even with $133K in the bank Syre faced problems with money right away. The design wasn’t finalized, engineering was still only sort of half-conceived at outset, and Spivey says he was “misled” by Apple’s Mi team and also had to spend a lot on simply locking down nanos for backers who selected a reward level where the iPod was included.

Since both these projects were conceived and funded, Kickstarter has made considerable changes to the way it handles hardware projects. The site is much more cautious in approving hardware campaigns to go live on the site, and requires that a functional prototype exist in each case. Generally speaking, far more hardware projects over the past year have been production-ready on Kickstarter than ever before, which is a good thing for the site, for backers, and ultimately for founders and creators as well. New rules or not, however, failure is still bound to be a flip side of this kind of startup funding (just as it is with traditional methods), and there’s a lot to be learned from the projects that go wrong.