Michael Shapiro isn’t the sort of person I’d expect to circumvent the gatekeepers of traditional journalism. He’s a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism, and he said he’s been published in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Sports Illustrated — in other words, he seems to be on pretty good terms with those gatekeepers.

Yet Shapiro is launching a new journalism startup called The Big Roundtable. The reason? He said that there are a lot of untested assumptions in the journalism world. As a parallel, he pointed to book publishing, where he said it was long believed that “black people don’t buy books.” There was, in fact, “this whole sub rosa world” of independent black book stores, with its own bestsellers like Iceberg Slim‘s Pimp: The Story Of My Life. Yet traditional publishers had no idea that world existed until the mainstream success of writers like Terry McMillan in the 1990s.

Similarly, Shapiro isn’t criticizing anyone in particular, but he said that submitting to the shrinking number of magazines that support long-form journalism means subjecting yourself to the taste of individual editors. He said he’s often asked by students and colleagues whether the New Yorker or a similar magazine might be interested in a particular story: “The answer is probably not. This is not the era in which I came of age.”

The web has spawned new venues for selling that long-form journalism, like the Atavist, Byliner, and Amazon’s Kindle Singles program, but Shapiro said they’re still applying the same editorial model. With The Big Roundtable, he hopes to do things differently. Shapiro has assembled a group of 50 readers, who are supposed to vet the stories. The first 1,000 words of each submission are sent to a subset of those readers, who are then asked whether they’d read more. (That’s all they’re asked — Shapiro said that in earlier versions of the system, readers offered more detailed feedback, but “it felt like homework” and “it quickly devolved into workshopping — you know, ‘I wouldn’t choose a semicolon here.'”)

If someone in that first group likes the excerpt, then it’s passed to a second group, and if someone likes it there, only then does an editor — specifically Mike Hoyt, executive editor of the Columbia Journalism review — start working with the author. Ultimately, Shapiro plans to sell a new nonfiction novella on the site every week, and the writer will get $1 from each sale.

Hopefully, this will allow The Big Roundtable to find work that didn’t catch the attention of particular editors but will still resonate with some readers. In that vein, Shapiro is looking for finished pieces rather than commissioning articles in advance — this should be a story that someone had to write, and they just haven’t found a home for it.

“If you’re going to say, ‘Well, I don’t know, I want to take my idea to some place where they can pay in advance,’ my response is: Go with God,” Shapiro said.

He also said he wants to expand the reading group from 50 people to “hundreds”, with a broad set of tastes and experiences, but Shapiro emphasized that it’s not quite the same thing as crowdsourcing.

“The thing about crowdsourcing is, it’s a crowd,” he said. “By its very nature it’s a huge, undifferentiated bunch of people.”

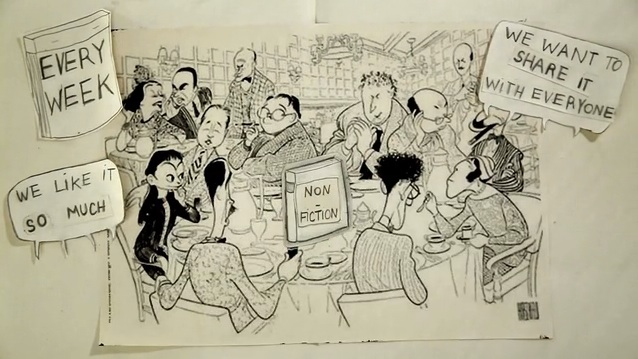

To illustrate his point, he mentioned the Literary Digest, a magazine that, in 1936, polled millions of people and as a result predicted that Alfred Landon would beat Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the presidential election — which was completely wrong. Shapiro’s point: That it’s less important to have an enormous group of readers, and more important to make sure that it’s the right mix. Put another way, Shapiro is emulating the Algonquin Round Table (a famous group of writers) and “scaling it out intellectually.”

To help fund The Big Roundatble’s costs, Shapiro has been raising money on Kickstarter. He recently passed his $5,000 target, but he said he deliberately set the goal low to make sure that he would meet it. He’s hoping to raise more money, which would presumably support The Big Roundtable for a longer period of time and allow it to get a little more ambitious. Shapiro said he’s going to be exploring other funding options, too.

“I’ll be looking at things like grants or investors to establish a real, ongoing laboratory, a laboratory in which … this is all to be shared,” Shapiro said. “I’m welcoming competition. If this spawns more digital publishing ventures based upon our knowledge, then I will believe that we are succeeding.”