While America’s political and business elite are pressing Congress to ease high-skilled immigration laws, a new study argues that foreign workers aren’t necessarily better or brighter. “The immigrant workers, especially those who first came to the United States as foreign students, are in general of no higher talent than the Americans, as measured by salary, patent filings, dissertation awards, and quality of academic program,” writes University Of California-Davis professor, Norman Matloff.

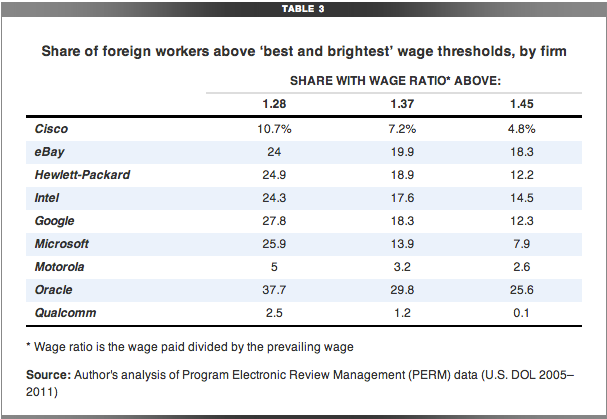

While technology leaders, such as Bill Gates, often complain that they must bait the best foreign workers with luxurious salaries, Matloff says that data doesn’t back this up. To illustrate just how little big tech companies actually value foreign workers, he presents a graph of the share of percentage of foreign workers that make substantially more than their native colleagues. At Google, for instance, only 12% of foreign workers are making 1.45 times the average worker in their field.

Matloff, a noted critic of high-skilled H1-B visa reform, finds that because there is no statistical difference in economic output between foreign and native workers, the idea of a shortage of high-skilled workers is a myth. “One of the industry’s most effective public relations tacks has been to claim that too few Americans major in STEM fields in college,” he argues.

Instead, foreign immigrants have saturated the market, pushing science, technology, engineering, and mathematics students onto other career paths. Quoting a study by a team of Berkeley economists, “…high-tech engineers and managers have experienced lower wage growth than their counterparts nationally. …Why hasn’t the growth of high-tech wages kept up?…Foreign students are an important part of the story.”

Posh Wall Street jobs for American STEM students are fueling the so-called “diversion” of STEM students away from technology careers. Between 2003 and 2006, the share of MIT grads going into financial services nearly doubled, from 13% to 25%. “If you’re a high math student in America, from a purely economic point of view, it’s crazy to go into STEM,” said Georgetown University researcher Anthony Carnevale.

As a result of the overwhelming influx, Matloff argues that foreign immigrants became a kind of “indentured servant,” forced to work for lower pay and less legal protections (a concern also expressed by industry unions).

Matloff’s study is sure to take a lot of heat, especially because he doesn’t take into account foreign entrepreneurs, who founded a huge chunk of influential technology corporation, from Google to AT&T. Matloff writes that he didn’t factor in the impact of entrepreneurs, because “the value of each of these indicators in assessing innovation is problematic. The difficulty with focusing on entrepreneurship is that one doesn’t know what kind of business is involved.”

Perhaps the take-away point is that the United States, at the very least, needs a “startup visa,” which allows hungry, innovative foreigners to start their own companies, without a sponsoring business. Senator Jerry Moran (CrunchGov Grade: A) recently introduced legislation to make this a reality, the Startup Act 3.0.

Either way, Matloff’s study is sure to spark a furious debate, as immigration reform continues to be top-of-mind for the US Congress.