Google is sounding a warning klaxon about a proposed law change in Germany which aims to strengthen copyright law for press publishers by requiring search engines and online news aggregators to pay a royalty to display snippets of copyrighted text — such as the first paragraph of an article displayed within a Google News search. If the ancillary copyright law passes, fines would be imposed for unlicensed use of publishers’ snippets.

The draft ancillary copyright law (online here in German) gets an expert hearing in a legal committee today, ahead of the second reading (German law requires three readings before a law can be passed), and is backed by the majority of the governing coalition — having being included in the coalition agreement between the Christian Democratic Union and the Free Democratic Party.

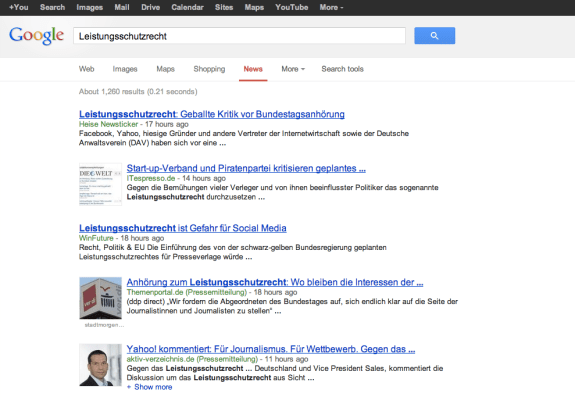

Currently displaying text snippets is free and legal in Germany so Google argues that the proposed amendement is a complete legal reversal. The issue is known as ‘Leistungsschutzrecht für Presseverleger‘ in German, and has also colloquially been dubbed a ‘Google tax’.

Mountain View is of course ideologically opposed to the proposal — calling it a “bad law” and arguing that it breaks the “founding principle” of the Web’s hyperlink-based architecture. From a business perspective the company questions why it should have to pay for helping publishers to acquire readers. “We are bringing massive traffic to the publishers’ websites,” Google Germany spokesman Dr. Ralf Bremer told TechCrunch. “We cannot see a reason why we should pay them for bringing them the readers.”

Setting aside the obvious inconvenience to its business, Google argues that the law will be damaging for web users because it will make it harder for them to find German documents because the context provided through use of snippets will be lost. Why should German publishers be treated differently to other publishers, it says. There’s surely little doubt that Google would refuse to pay for the snippets if the law passes — you can imagine the company viewing that path as a slippery slope leading to an avalanche of copyright claims falling on its head — although at this point Google said it is not in a position to specify how it will respond if the law passes.

What’s certain is that Mountain View is being directly targeted by the proposed law. It specifically cites search engines as the target entity for the additional publisher “protection” — and Google is far and away the dominant search engine in Germany. But Mountain View claims the law is not just going to cause it pain — but could also apply more broadly to other online companies and startups that make use of text snippets.

The text of the current draft of the law states that the proposed protection “is only against systematic access to the publishing performance by the search engine providers” (translated from German via Google Translate) — and goes on to add that other web users are not included (“such as Blogger, other industrial companies in the economy, Associations, law firms and private and voluntary users”). However Google points out that the wording of the draft law also references “suppliers of search engines and suppliers of such services, who process content similar to search engines” as falling within its remit — a vague definition that it says could even apply to social networks.

“The question — which services are meant by the latter [portion of the draft law’s wording] — is controversially debated. The latest interpretations, we have seen, assume that Twitter, Facebook and the like will also be affected,” said Bremer. He argues that every web service or information-based startup that wants to use publishers’ snippets could potentially be affected.

“As soon as this law comes into place there will have to changes made by every platform working on the web,” he said. “It’s not just a law about Google… it’s about the entire startup scene that we have in Germany, and especially in Berlin. Because potentially every company that works on the web has to deal with snippets, more or less, in their business.”

“From the day this law comes into place, every company that wants to use these snippets… would have to reach out to publishers and call them individually — ‘hi, can you please allow me to use your snippets and what do I have to pay for that?’ And if you understand there are more than 1,200 publishers you can imagine that it is simply not possible,” he added.

Google is not alone in its opposition to the proposal. The German Association of Startups has put out a statement opposing the current proposal — in which it writes (translated via Google Translate): “The current proposed intellectual property right for press publishers has strong potential harm to Internet start-ups in Germany . Regulations such as the related right for press publishers slow innovation in Germany and lead to a competitive disadvantage, particularly in an international comparison.”

There is also political opposition — several of the smaller parties in the government put out a joint statement against the law. And a coalition of 25 German companies has also come out against it, to name a few of those opposed.

Another problem with the draft law, as Google and other opponents tell it, are the myriad legal gray areas it throws up. For example it does not nail down the definition of a snippet — meaning it could be left to courts to decide whether a snippet means a few sentences, a few words or even just a URL. “It is not even sure the pure hyperlinks are free because some hyperlinks contain part of the text,” said Bremer.

If the law is passed — which is certainly possible, despite widespread opposition, as it has the backing of the governing coalition — it’s unclear what Google would do at this point, i.e. in terms of whether they would have to pull German snippets from search results. “We have to look at the final wording, before we can come forward with a decision,” said Bremer.

According to Bremer Germany’s big publishing houses originally lobbied for the law change. He describes them as politically well connected — and also points out that it’s an election year in Germany this year. “Pressure from the publishers is really high to get this law done within the coming months,” he said.

Bremer said today’s expert hearing — which will involve input from a panel of nine experts (ostensibly independent but three of whom Google argues “belong to the publishers’ lobby”) and at which Mountain View has not been invited to speak — could be “the last change to get this law off the table or to shape it in a way that is not so dangerous today for the web architecture”. Google’s hope, says Bremer, is for the governing coalition to listen to the views of the independent experts and think again.

“The arguments against this law are very strong. The arguments for this law are very weak,” he added.

So what about the arguments for the proposed law? German publisher Axel Springer — whose publications include the newspapers Die Welt and Bild — is an active supporter of the proposals. Asked to respond to Google’s arguments against the copyright extension, Christoph Keese, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations and Public Affairs for the company and chair of the joint copyright committee of Germany’s newspaper and magazine association, told TechCrunch that “Google’s statements are unfair and disproportionate” and “in no way represent what this law is really about”.

Keese also rebutted criticisms about the potential scope of the law, claiming it will “have no effect on the right to quote or link”, and that “citations and links stay free”.

He continued:

It is neither “mad” nor will it harm users, the internet, open society or information pluralism. To the contrary: This reform brings German copyright law much closer to the US concept where publishers traditionally enjoy strong rights. Over here publishers have no rights on their own to this very date even though music, film, television and performing arts have enjoyed ancillary rights since the mid sixties.

What this reform does is very simple: It establishes on opt-in model for commercial copies of content and parts of content. This will lead to license agreements between publishers and aggregators.

On the specific point about the impact on startups, Keese argued that being as the pricing for licensing the snippets will be “reasonable” then “no business model shall be discouraged”, adding:

We have carefully considered impact on the thriving start-up culture especially in Berlin. There will be no negative effects. To the contrary: New innovative business models will arrive built on legally licensed content. Even before the law comes to effect we observe rising demand by start ups seeking investment and licensing opportunities.

This law will help establish a market for aggregator content which at the moment is non-existent. Google (>90% market share) displays monopolistic behavior by trying to impose its legal view on publishers to protect its margin. While publishers respect Google’s technological and entrepreneurial achievements we are not prepared to give content away for free. Search indexing is more than welcome. But aggregators have gone far beyond that.

The royalty rate that publishers would charge has not been determined yet. On the question of pricing, Keese said: “Parliament has not decided yet if it wants the right to be exercised through a collecting society or not. Absent this decision it would be premature to speculate about pricing.”