It started with an assumption, really. Snapchat, a photo-sharing application that auto-destroys images seconds after being opened, launched in September 2011 with zero media coverage. A homegrown product, built by two Stanford guys, grew to now see over 50 million snaps per day today. In fact, Facebook launched a clone of the app just Friday.

It wasn’t until the company made its first milestone announcement, nine months after launch, that the media picked up the story. The New York Times’ Nick Bilton whipped out all this cute PEW research on sexting in adults and teens, and referenced “suggestive” marketing materials and even pointed out the app’s “mild sexual content or nudity” warning.

From that moment on, whether in milestone achievements, feature and expansion announcements, or stories about Facebook’s new Snapchat clone, Snapchat was branded a sexting app.

The Myth

Snapchat is a lot like Pinterest. Coverage of the service came way later than its troves of users.

Being late, and of a different generation than the majority of the app’s users, many members of the media jumped on the click-happy sexting story instead of the truth.

“We were worried that usage and growth would decrease if the sexting publicity made Snapchatters feel uncomfortable,” said co-founder Evan Spiegel. “In hindsight we shouldn’t have underestimated the loyalty and creativity of our community. The uptake has been remarkable.”

And it has been. Snapchat is currently sending over 50 million snaps per day, with over 1 billion sent in total. Plus, word on the street is that Snapchat is raising a round of funding between $8 and $10 million. And up until this Friday, there were also rumors that Facebook was launching a clone, and it did.

Snapchat suddenly became a huge deal, and the urge to understand it (and explain its success) became important. And in the mind of tech reporters, the blogosphere, and the general media, there’s only one explanation for using an app that sends and then destroys self-portraits: sexting.

And the app’s marketing materials and app user warning didn’t help. The original screenshots on display in the App Store were of pretty girls in bikinis. The app warned of “Mature/Suggestive Themes” and “Infrequent/Mild Sexual Content or Nudity.”

“To be fair, our early marketing materials were a bit amateurish. I took those photos on the beach with friends,” said Spiegel. “They were fun and playful at the time, but didn’t represent how the app was actually being used.”

The Conspiracy

Whatever Spiegel’s intentions, the media ran with the sexting story. After all, in a media that loves turning a sclerotic eye on made-up teenage perversity (“rainbow parties,” “jenkem”), Snapchat was solid gold.

Best of all, this Snap-sex trend was lining up with the evidence. There was even a Tumblr site called Snapchat Sluts documenting one man’s sexting rampage.

The confusion is understandable, given the nature of the app and its self-destructing pictures. The media are a generation of tech users that are incredibly obsessed with privacy. We would make this logical leap in the wake of Anthony Weiner and every teenage girl who’s ended up with a nude pic on the internet.

In any case, story after story popped up about Snapchat, all of which mentioned it’s popularity among sexting teens.

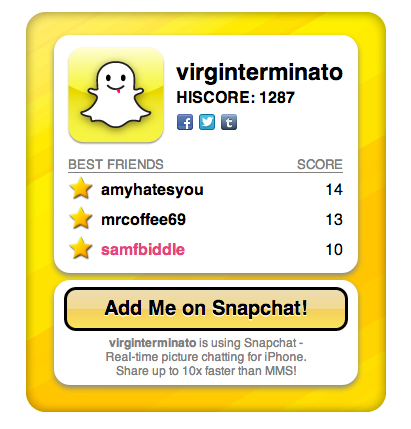

Turns out, almost every reporter to use both the words Snapchat and sexting in an article is a user on Snapchat. I know this because Buzzfeed discovered Snapchat has public user profiles on the internet, showing users top three most frequently snapped-with friends and their Snapchat score (a count of Snaps sent and received on the platform).

These writers fall into two categories: real users who are active on the platform (which is clear from their scores), and users who downloaded the app , used it once or twice to better understand it, and then wrote a story on it.

I learned that the former group is predominantly chatting with each other. For example, Katie Notopolous of BuzzFeed, who wrote this story about Snapchat’s super risky public profiles, chats with Gawker’s Max Read (who wrote this) and with a Gizmodo writer Sam Biddle. Sam snaps occasionally with less active user Joel Johnson, longtime Gizmodo employee.

I learned that the former group is predominantly chatting with each other. For example, Katie Notopolous of BuzzFeed, who wrote this story about Snapchat’s super risky public profiles, chats with Gawker’s Max Read (who wrote this) and with a Gizmodo writer Sam Biddle. Sam snaps occasionally with less active user Joel Johnson, longtime Gizmodo employee.

Then there’s the folks who’ve written about Snapchat being the sexting app, but barely ever use it, like Gizmodo’s Adrian Covert (story), GigaOm’s Eliza Kern (story), CNET’s Jason Parker (story), and the NYT’s Nick Bilton (story). Yep, the same guy who started the myth doesn’t even use the app.

There are two conclusions we can make. The first is that the same folks who serve you a round of tech news with your morning coffee and bagel are also in a Snapchat sexting ring. The second option is that the very same people who have repeatedly assumed that Snapchat is for sexting, and propagated that myth, don’t use Snapchat for sexting at all.

Weird, huh?

The Facts

“Social media has generally relied on surveillance as the mechanism for stimulating feelings of connectedness,” Spiegel explained. “We’ve found that using Snapchat to live and share in the moment can make you feel like you’re face-to-face with a friend even if they’re on another continent.”

Truth is, there can never be any evidence that Snapchat is used primarily for sexting because the service deletes photos immediately after they’re opened, both from the recipient’s phone and from their servers. This means that there can not be any real evidence for or against sexting on Snapchat.

And you know what? By a very small percentage of users, Snapchat probably is used for sexting for a very small percentage of the time.

When you’re sending over 50 million snaps a day, a few of them are bound to be of naughty bits. But 80 percent of those snaps are sent during the day, with a spike during school hours. Whatever the sexting stats may be, they’re more likely using Snapchat to cheat on tests than to sext.

Snapchat wasn’t built for sexting, which seems clear from the fact that pictures self-destruct in less time than it takes to fully enjoy a nude pic. But some see this as a security feature for sexting, which is a matter of opinion.

However, the UI (which is actually quite amateur) doesn’t really suggest “Let’s Get It On,” with lots of yellow and bubbly blue and a friendly ghost for a mascot. Valid, but still an opinion, and one which opponents can argue is meant to lure young demographics to the sexting platform. Let’s, instead, focus on the evidence.

The user warning on the app, referenced in many Snapchat articles, means nothing. Every photo sharing app has one like it. Check out Instagram’s.

Also often referenced, the “suggestive” marketing images (which have since been swapped for new ones) were a mistake, but not one worth crucifying the app for.

And let’s not forget that Facebook just cloned this app with Poke. Is Facebook really trying to tap into teen sexting? Probably not. They’re tapping into something much bigger than that.

The Real Story

There is a big difference between the way a 24-year-old and a 19-year-old see social networking. It seems like a small gap, but some crucial changes happened during this time that has most certainly differentiated today’s teenager from yesterday’s.

The first was the release of the iPhone in 2007, which changed photo-sharing as we know it. People take photos of anything and everything now, because their camera is in their pocket, and uploading those photos to the internet takes three clicks, tops.

The second crucial change was the public opening of Facebook in 2006.

My sister is 19 and I am 24. I was 19 when the iPhone came out, and I was a senior in high school when I first got Facebook, a year before it launched publicly.

My sister was 14 when the iPhone came out, first got on Facebook at age 13. Unlike myself, her friends have had smartphones (and have been taking pictures with them) throughout their entire high school (and now college) career. And many of them are now documented neatly on her Timeline.

The pressure to maintain an appropriate, attractive presence on the Internet has weighed on me since college. It’s been with her for her entire life.

This is the difference between the people writing about Snapchat and the people using it.

My sister is one of the biggest Snapchat users I know, and the pictures she sends me of herself are awful. That’s not the usual for her. She’s 19, and will force our family to stand in 100-degree weather for hours to get the perfect shot of her smile.

The snaps she sends me could be called ugly — her on the porch, in the dark, with a goofy look on her face. If she was posting this on Facebook, or Instagram, or even sending it to me on MMS, it wouldn’t be the same picture. It wouldn’t be so ugly.

But there’s an intimacy that comes with Snapchat that makes those pictures safe, and much more enjoyable than seeing yet another perfect picture of my sister on Facebook. I see her as she really is.

It’s about as real as you can get in a world where everything happens through an all-seeing eye of 1′s and 0′s.