Earlier this week, Uber faced another challenge in its effort to disrupt urban transportation, as Chicago’s Business Affairs and Consumer Protection department proposed new regulations that would prohibit car services from using electronic devices to measure the time and distance traveled as a way to determine fares for riders.

The move was just the latest in a series of similar setbacks, as government agencies and regulators around the country have scrutinized the service as it enters new markets.

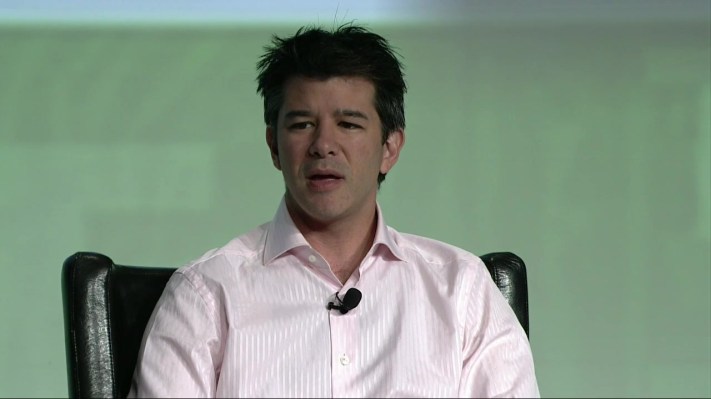

Recent moves have suggested that Uber — which has spent the last two years operating without any serious disruptions to its service — might be vulnerable after all. It backed away from offering its UberTAXI service in New York City after failing to reach agreement with the Taxi and Limousine Commission there.* And in Chicago, CEO Travis Kalanick tells us that if the BACP’s rules go through, it will no longer be able to offer its black car service in that market.

All of that is bad news for Uber, sure, but it also bodes ill for a number of other startups that are seeking to make more efficient use of assets users already own. In short, Uber is merely paving the way for a number of innovative startups that are seeking to take on major incumbents in regulated industries, and its success or failure in taking on local governments could shadow the overall success of collaborative consumption as a concept.

Sharing economy at stake?

Uber is no longer the scrappy underdog it once was, and so it’s facing a bit of backlash lately. That’s partly due to its “Don’t ask permission” mantra when it comes to offering new services or entering new markets. It’s due to the company’s propensity to institute “surge pricing” just when its riders need it most. But it’s also due to the fact that at its core, Uber is seen as a luxury service for those who can’t afford to use it.

But one thing that Uber does extraordinarily well is to take existing assets that are underused — in this case, black cars that are otherwise waiting for clients to call — and puts them to more efficient use. In that way, it’s really not that much different than Airbnb, or Getaround, or TaskRabbit, or any other marketplace in the so-called “sharing economy.”

Apartment shares and rentals existed before Airbnb, but there was no online marketplace to make them easy to find. Generally you had to know someone who knew someone, or you had to do an exhaustive search on Craigslist. There was no way to book online, and certainly no way to guarantee that you wouldn’t be left out in the cold when you showed up. In the same way, ride-sharing existed before Lyft or SideCar — but it was mostly limited to community carpooling boards at companies or universities. And people have always wanted easier access to car rentals, but there was little way for them to make use of their neighbors’ dormant automobiles before Getaround and RelayRides came around.

The wild, wild west

Just as Uber aimed to connect those who needed transportation with those who can provide it, each of those services provide marketplaces for connecting haves and have-nots. And each of those services seeks to provide alternatives to highly regulated incumbent service providers in the hotel, transportation, and car rental industries.

Just as Uber aimed to connect those who needed transportation with those who can provide it, each of those services provide marketplaces for connecting haves and have-nots. And each of those services seeks to provide alternatives to highly regulated incumbent service providers in the hotel, transportation, and car rental industries.

I don’t think any of the startups above welcome regulation, but unregulated industries are really only as good as the actors playing in them. That’s the lesson we learned from Airbnb’s public relations debacle last summer, after a host had her home trashed and looted by Airbnb guests. For its part, Airbnb moved quickly to double down and provide better customer service, while also taking out an insurance policy to ensure peace of mind among its communities.

Since then, most startups in the space have followed suit: Getting an insurance policy to protect users from having their assets stolen, damaged, or destroyed when rented out has become table stakes, whether you’re talking about Airbnb or Getaround. Running extensive background checks on users that provide services has also become a common practice for startups like TaskRabbit or Lyft. With a lack of regulations governing them, these companies are seeking to go above and beyond — in part to prove that they can be self-regulating and don’t need the tentacles of government slithering over them.

At the same time, incumbents cry foul when they see what startups are getting away with. Airbnb hosts don’t pay hotel taxes. You don’t have to save up for a medallion to be a Lyft driver. Cars on Getaround aren’t held to any safety or maintenance checks. There are no regulations designed to ensure health and safety. And as a result, they don’t have to deal with all of the costs involved with being an incumbent.

Thriving In The Face Of Regulation

The other side of the argument is that startups are able to create efficiencies because they are moving faster than today’s regulators. Uber’s issues in Chicago are a great example: There are no regulations today around using a mobile phone or GPS to determine fares, because that technology wasn’t being widely used until two years ago.

For the first time, we have the tools to provide truly efficient marketplaces for a number of new markets. There’s no longer a need to over-build hotel capacity or finance entire fleets of rental vehicles when regular people have extra rooms in their apartments or cars that are not being driven. There’s a huge amount of spare inventory that can be better utilized, and now there’s technology available to take advantage of that.

The problem with regulating these companies is that government agencies are ill-equipped to understand existing technologies and recognize future trends before they happen. All of which is why I hope the startups providing these marketplaces aren’t regulated out of existence by governments seeking to provide a level playing field for incumbents. Not just for the sake of the tech industry, but for all of us who are taking advantage of the freedom and flexibility they provide.

[Wild West Image Source]