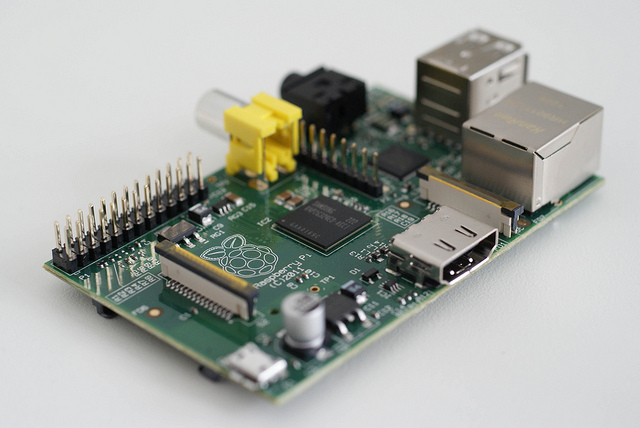

If you’re a hardware hacker who knows your apples you’ll have heard of the Raspberry Pi – and maybe even bought one already. It’s the super cheap mini-computer which featured prominently at our Hackathon event last month.

But there’s more to the Pi than a decent processor at bargain basement prices ($35/a $25 version is coming soon). We got the chance to chat to Eben Upton, founder and trustee of the not-for-profit Raspberry Pi Foundation — and the man responsible for the overall software and hardware architecture of the Pi – about the very big-hearted ambition behind the project.

TC: What was your motivation in creating Raspberry Pi – what were you setting out to try and achieve?

Eben: I was working at the university in Cambridge about six years ago and I had this awful experience of seeing the number of people applying for Computer Science every year going down and the sorts of things they’d have to do getting less and less impressive. Ever since then there’s been an effort largely focused around the computer centre in Cambridge to develop some sort of system, some sort of platform for giving kids the opportunity to get involved in programming.

And this went through a number of iterations, and during that process I joined Broadcom as a chip architect, and fortunately it turns out that there’s a Broadcom chip that I was involved in designing which has pretty much exactly all the features you need for a low cost programming platform for kids. And that’s where the whole thing came from. First this realisation we had a problem and then some sort of slightly contrived good luck in having access to a platform that we could use to make this.

We’ve always had this idea that you’re not going to appeal to children with a platform that can’t do anything interesting, that can’t do anything recognisably modern. So one of the nice things about Raspberry Pi is we’ve ended up with a platform that can play 1080p – can play Blueray quality video; that’s got more graphical power than a Nintendo Wii; it’s something which is recognisable – it’s not a retro machine. It may look a little retro but in terms of performance it’s a recognisably modern piece of hardware.

TC: Did you attribute the decline in programming skills to a lack of hack-friendly devices?

Eben: I grew up with a computer I could program. I learnt to program not because anyone ever thought of teaching me to program and I think a lot of people of the same generation had the same experience – an experience that is transparently not available to children now.

Not every child has a PC, even the ones who do have a PC, the PC is not a particularly friendly environment for those who want to program. So our hypothesis is this is what’s happened: we started to lose those programmable 8-bit machines of the late 80s — that then led in quick succession to the loss first of kids who were programming, then it was undergraduates who were programing, and then of graduate recruits to industry who were programming.

We’ve got to be very careful not to be nostalgic about those machines. They weren’t the most user-friendly machines, and the stuff you could do was not as interesting and sophisticated as what you can do with a modern machine but they did have this property that you turn them on and the first thing you’ve got to do was choose – if you’re not going to program them – you first had to choose not to program them. The very first thing you could do with them when you turn them on was to program them so we’ve got this hypothesis — and you can really see the whole Raspberry Pi program as being a test of this hypothesis, of looking to see whether this hypothesis is true.

TC: Isn’t it a bit of a paradox that we’re surrounded by so much technology and yet engineering skills are declining?

Eben: These are appliances; your phone is an appliance, your tablet generally is an appliance. I am a little sceptical about tablets generally in education because they’re appliances – they’re devices for consuming, not devices for producing. Producing is where the value is, producing is where the fun is. Maybe I’m biased but I think producing is where the fun is and certainly it’s where the money is so you’re right, it is a paradox but fortunately — these devices have commoditised processors like the BCM2835 which is the Broadcom chip that we use – we own the existence of that device to the prevalence of very high end smartphones because it is a very high end smartphone chip.

And also we can piggyback. We can piggyback on the existence of these things but I don’t think we can just rely on a smartphone in every pocket to give us another generation of people who do interesting stuff with computers, the kind of people I went to university with.

TC: What are your total sales of the Raspberry Pi to date?

Eben: Currently we’ve shipped about 400,000 – that’s since March, we expect to pass the half million point in the next month or so; we expect to have sold about a million — looking at the projections — about 12 months in so in our first year we will have sold about a million.

TC: How many Pis did you think you might be able to sell when you started the project?

Eben: A thousand. I’m not kidding. A thousand. That was what we planned for. We thought – it’s a really great little device, so we figured maybe if we got really lucky then over the entire life of the product, over two or three years, we might sell 10,000 maybe. And then I guess by Christmas of last year we got our first hint that we might get past 10,000. We have a very large community on our website and the size of that community was getting to the point where we were thinking we might sell 10,000 quite quickly – as it was we sold 100,000 on the day we launched. And then a million in the first year, so that was a surprise.

TC: Who did you imagine would be buying the Pi — and who is actually buying it?

Eben: We were thinking about kids, the whole thing was about kids. What we’ve found is that only a minority of the units we’ve sold have been sold to kids. At the moment — to date – they’ve been mostly sold to very technically capable adults — to hackers, makers, geeks, people like me.

But we’ve sold so many of them, that even though that may be only 10 or 20 percent of them have been sold to kids, 10 or 20 percent is still tens of thousands of units so that’s kind of nice, so we are already reaching kids. But I think what we’d not realised, what we’d not anticipated is the massive interest in the maker community — so there’s our original market which was kids, there’s the market which we actually ended up with mostly which is makers, and then there’s the market which we’re starting to just get a bit of a sniff of now – which is developing world productivity machines – actually people using these as general purpose computers in the developing world. But I think that’s got an enormous amount of potential to really go and democratise access to information technology in places where maybe people have just bought their first television – emerging middle class in Africa — this is a little additional expense which will connect to your television and help you get more value out of that investment.

TC: How were you able to make the Pi so cheap? What made that possible now?

Eben: I guess there are several things. One obviously we have a good relationship with Broadcom; historically it’s not been possible to build these things in small quantities for a decent price. Historically there have been things that are available in small quantities at a very high price and things that are available in very large quantities at a small price, I guess we have a number of technical innovations, business model innovations, advantageous relationships which allowed us to start small but start cheap. There were a lot of boards like Raspberry Pi in the $200 range but not a lot in the $25 to $35 range.

You’ve got to see [price] as our differentiator. The big impressive thing we’ve done, as far as I’m concerned, is to make this stuff cheap and available – we’re not making anything that didn’t exist before, but we’re making a thing that previously was very expensive – and also we’re very lucky with the chip. Obviously I was in the design team so I’m not exactly impartial but it is a very strong chip, and a very cost effective chip.

[We also had] a bit of a think about all the things that people typically already have – so most people have a screen of some sort; most people have a television, even if they don’t have a flat panel television you can usually, these days you can go down to the tip and get yourself a old CRT television basically for free; then on the power supply mobile phone charger — we mostly have mobile phones, they all have standard chargers now so we use a mobile phone charger; storage we use an SD card; the mouse and keyboard I suppose are the only things that you might not have – but most people can scrounge a USB mouse and keyboard from somewhere, even if you can’t they are very very cheap, so the idea was to make the thing that people don’t have and to try and make it in a way that will make use of things they already do have.

TC: Is anyone else trying to do this now?

Eben: We have seen some people trying to do this in China – possibly because we’re weak in China so it’s kind of hard to get hold of Pis there today. We’ve seen a few people try to do some, we haven’t really seen anyone really with a shipping product yet – within a factor of two of the same price. There are some people who crept down into the high $60s probably with devices which are a little less powerful than ours. There are people up in the – I can point you to a board you can buy for $130 which is better than us. And that’s always been the case – there have always been these more expensive but more powerful boards but they’re four times the price. I guess the innovation we’ve seen since Pi launched is there are people who are almost as good as us and only twice as expensive so that’s progress I suppose. And I think probably if we were to stand still for two or three years – then I would imagine it would be possible for someone to catch us, so we do have our eye on the competition and we’re trying very hard not to be complacent.

TC: Did you consider setting up as a business, rather than as a not-for-profit?

Eben: It’s easier to do as a charity because – when you’re dealing with partners – people know that you’re on the level, particularly when you’re at small volume. If we were at our volume now – if we’d know all along that we would hit our current volume – it would have been feasible for us, I still don’t think we’d have wanted to, but it might have been feasible for us to do this on a commercial basis. But when you’re dealing with a thousand and 10,000 those are small enough numbers that it’s very hard for you to go and get the components that you need to build the device on these financial terms – you’ll just be penalised by your supplier for making small orders because they’re low margin. Because we were able to appeal to all our providers, and say look we’re not trying to make a quick buck here, we’re trying to do something which is genuinely valuable. Obviously most of our partners and suppliers are in the tech industry and then we have a story about how the tech industry’s going to disintegrate in the next 20 or 30 years if we don’t do something. Because we were a not-for-profit, because we had a sense of mission those guys could – it gave them a reason to deal with us on good terms even though we were kind of small.

TC: Where is the Pi most popular?

Eben: The UK. Britain’s still our largest per capita market, if only slightly behind the US for total unit shipments. The US is our largest single market but then again they have five times as many people as the UK. The UK has the largest total installed base of Pi units – in the about 200,000 unit range.

We’ve had a lot of support from the media [in the UK] – we have done extremely well. That sense that we do have a heritage here; we invented the computer in a lot of ways so I think it has helped we had this amazing industry in the 1980s, this flowing of home computer innovation which eventually led to ARM which is probably our flagship UK tech company, so I think it taps into something.

We’re quite strong in Northern Europe, Germany, Russia… Little pockets in Australia, New Zealand. Where I think we would like to be stronger is in South America but those are places where the main barriers are tariff and shipment barriers. I believe today if you buy a Raspberry Pi in India, it’s shipped to you from Singapore and that means that you’re paying a big wedge of tariff and a big wedge of courier charges, so it’s a similar situation with Raspberry Pi in Brazil, so those problems are being worked on by our distributors.

We’ve still don’t really have much presence in China – and I think that’s really a language barrier and information issue and we’re working on ways of addressing that.

And I guess that probably leaves Africa – but it’s very strong in South Africa. We’re looking to use South Africa as a springboard to increasingly affluent per capita cities of sub-Saharan Africa. There’s a lot of tech in Ghana. There’s a lot of tech in a lot of these places and an emerging middle class who we think are ready for this kind of innovation.

There’s a lot of countries looking at it as a way – as a tool to try and make sure they still have an industry in 20 years time.

TC: Can you give me some examples of the most interesting things you’ve seen the Pi used for?

Eben: A guy called David Akerman put one on a high altitude weather balloon in southern England to send back pictures from 40 kilometres up so it looks like you might as well be in space, so that was pretty impressive.

What is really nice thing is we’re starting to see kids using them. People send us pictures of their kids learning to program on the Pi… it’s very very sweet. Often right now a lot of these are the children of engineers. A big thing that’s happened is that engineers of my age are using it as a way to talk to their kids, as a way to share their enthusiasm for engineering with their children — and that’s really sweet, we see a lot of these pictures. It is really heart-warming.

TC: Have you had much interest from schools so far?

Eben: Even at the end of the last academic year these were in quite short supply, so it’s only really in the last two or three months you‘ve been able to buy them in large quantities – in kind of classroom sizes – so what we’re seeing is starting from about a month ago the start of the new school year, we’ve been seeing a lot of individual teachers, departments, the occasional school coming in and buying two units, five units, 10 units, 30 units. In different ways a classroom set – depending on how many people are going to share a machine. And a lot of these people are going to run after school clubs/activities – this is a device that’s cheap enough that it can be funded out of discretionary money rather than out of some central pot.

The [UK] government knows that the ICT curriculum is broken… [UK] schools for two years, this and next, have a lot of freedom in how they interpret their obligation to teach kids about computers and some of the best schools are using this as a fantastic opportunity. They’ve got a hole in their timetable now that they can fill with really productive useful teaching about computers rather than being hamstrung by this previous curriculum. It’s good. We’re participating in the program to develop a better curriculum for 2014 so the future’s actually looking bright for the first time in a little while.

TC: What’s next for the Foundation?

Eben: We are very focused on getting value out of the current platform. We’ve got 400,000 people who’ve got Raspberry Pis – the last thing we want to do is to move onto a whole new platform. I think we’re doing a lot of work on the software side to increase the performance… to try and get more value for those existing customers.

This is not the educational release of the Raspberry Pi. There will be a version, and we’re spending a lot of time and money on this at the moment, which has optimised performance for education and which has a package of teaching and learning materials built in.

We are also currently only shipping the $35 version which is the deluxe unit. We’re need to backfill and bring out the $25 version which is effectively the same thing but without the Ethernet. We plan to do that in the next couple of months so there will be a $25 version – which we think is going to be very good for these deeply embedded applications but for people who want to use wi-fi – for people who don’t need wired Ethernet, they can just plug a wi-fi dongle into it. They’re saving themselves a bit of money and they can spend that money on a wi-fi dongle.

I guess in the long term we want to do something new. If we’re still around in five years we’re not going to be shipping the same unit we’re shipping today. But I think in the immediate short term there’s no plan to move to a different chip.

TC: So in 15, 20 years’ time your hope is that people who learnt to code on the Pi will be powering the next wave of technology startups?

Eben: If we still have a functioning high tech economy when I’m old enough to draw a pension then that will be a good sign.

We’ve have so many modest little ambitions for this project all the way though. I wasn’t kidding when I said we thought we’d sell 1,000 units. Originally we used to say if we can just get a few more people applying to Cambridge to read Computer Science or improve a little bit the skills of the people who are already applying, or when we were feeling really optimistic we said what would be the dream outcome for us: a thousand more engineers a year in the UK. Last year that would have been our dream scenario, if we could have got a thousand more entering engineering degrees or apprenticeships. Graduating from those degrees or going into working apprenticeships… That would make a real difference to the UK economy and it would also make a real difference to a thousand people. A thousand people would end up with much better job lives than they would have if they’d done something else.

[Image: GijsbertPeijs]