It’s no secret that many deals have been struck and key relationships formed at TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington’s former house in Atherton. In case you aren’t familiar, Arrington threw epic parties at his home for the tech community in the early days of TechCrunch. Police were called, booze was flowing, people passed out. I don’t have enough fingers to count how many times I’ve spoken to a Silicon Valley entrepreneur or VC who said he or she used to frequent Mike’s house parties back in the day. Clearly this was the place to be for anyone looking to meet their next investor, acquirer, co-founder etc.

And that’s exactly what Box co-founders Dylan Smith and Aaron Levie were thinking when they showed up to Mike’s house in early February 2006 for the Naked Conversations TechCrunch Party. It was in Mike’s backyard where they met then Draper Fisher Jurvetson partner Emily Melton. Beers in hand (actually only Levie was of age-barely, so Smith was drinking water), the pair pitched Melton on their idea. She was so impressed and their passion for what they were building cloud storage, that she immediately introduced them to the DFJ partner covering SaaS and enterprise investments, Josh Stein, who months later led Box’s first round of institutional investment.

Smith and Levie credit this meeting as one of the key turning points for Box to become what it is now—a close to billion dollar enterprise cloud storage company with 11 million users, 80 percent of the Fortune 500 as customers, and $162 million in funding. In the company’s latest funding round in the Fall of 2011, the company was valued somewhere above $600 million, a number that could easily have jumped in the past 9 months. While two teenagers starting a tech company out of a garage isn’t that unique in the Silicon Valley world, Smith and Levie’s ability to create a valuable product from thousands of dollars, and instilling confidence in well-known VCs and companies is.

From Research Paper To Funding

The idea for Box originated from a research project that Levie, who was then a college student at USC, was working on in 2004. Levie’s project examined storage options and in the process of researching his paper he discovered how fragmented the market was. He called up 10 random businesses and asked how they are storing content and data and received ten different answers. Back then, Levie realized in his research that even though there were no iPhones, tablets or Android phones, people still wanted to access data from different places. These places just happened to be extinct technologies now, he adds, joking that the Palm Trio was back then a prime destination to find documents.

“The opportunity I saw was to build something that would change how you want to get your information,” he explains. At the time, many thought Gmail would be sufficient for storing data. But Levie felt there was a real business behind where to store data and this was in the cloud. The name Box came from his vision of storing data in a virtual box in the cloud.

During the Winter Break of 2004, Levie shared his idea with Smith. Both Smith and Levie had toyed around with startups in the past and had dreams of starting their own companies. The boys shared Levie’s passion for the cloud storage idea and by the Spring of 2005, Levie, Smith and his friends were actually developing a product. Box, at the time, was simply an online file storage service where users could pay to store files in the cloud.

This was all happening in between classes, says Smith, who was enrolled at Duke, and in order to fund the early days of Box in 2005, Smith invested $20,000 of money he earned playing online poker. The team actually launched the product in February of 2005 as a simple file storage product for both consumers and enterprises. Levie and Smith sent their pitches to the media and landed coverage on sites like Gizmodo, where they offered free storage incentives for new customers. The fledgling startup quickly accumulated a few customers and began its journey as a real service.

In the summer of 2005, Levie, Smith and the team housed themselves in Smith’s parents’ attic in Seattle and worked on accumulating more customers and developing the product. Smith’s younger brother did tech support, Levie said, and he and Smith tried to raise additional financing in Seattle. But this proved to be challenging at the time. “Seattle was lacking the Silicon Valley-Zuckerberg story. VCs and angels in Seattle were still repairing wounds from the Dot.com bust.”

Smith and Levie decided to take their roadshow national and began contacting angel investors outside of Seattle. One of those investors was Mark Cuban. Levie cold-called Cuban via email about Box, and got a response from the entrepreneur immediately. In the Fall of 2005, Cuban decided to put in $350,000.

Around the same time, Box was scaling fast and it got to the point where Levie and Smith realized that they could no longer attend school and manage the day-to-day activities of Box. Both Levie and Smith approached their parents about dropping out of college in December of 2005. While both Levie and Smith’s parents were supportive, Smith says he his mom was a little bit concerned about throwing the education away. It took some convincing, says Smith, but in the end he promised he would go back and earn the degree at some point.

Once the decision was made to leave their respective colleges, Aaron (then 21) and Smith (then 20) mutually agreed that Silicon Valley was the best place to be. The pair packed their bags and moved to Berkeley, California in early 2006, where Levie’s uncle rented them a small garage. As Smith recalled, both Levie and him worked and lived night and day out of the garage, soon joined by high school friends from Mercer Island, Jeff Queisser and Sam Ghods.

As for the product, Levie and Smith began to brainstorm ways in which to get the service to go viral, and decided to open up the file storage service for free. Smith says this was a key turning point for the company, which began soliciting customers with little sales efforts. In fact, Box was getting so much traffic that servers were breaking down. But in terms of the vision, Box was still a consumer and business company. As Levie explains users “interpreted what they were doing with Box in their own individual way. Some people thought it was backup, others found it a way to replace emails,” he says.

Then came that fateful Spring day at Arrington’s house, where Levie and Smith pitched Melton on their company. The boys had already decided they needed to raise a round, and were attempting to make connections with investors on Sand Hill Road, but the in with Stein at DFJ was able to speed up the process.

Stein recalls in one of his first meetings at Smith and Levie’s Berkeley garage, he had to step over enormous mound of stinky laundry, and was legitimately worried about the boys’ health in garage. But besides the pungent odor, he was immediately struck by how impressive the product was for a bootstrapped startup. “You could tell right away that this was a company that was very product-focused. Coming off the heels of storage failures of Xdrive, Aaron had come up with differentiated and distinctive vision for what product should do, what it should look like.” And what also impressed him was Dylan’s detailed insight into the startup’s business operations despite his youth.

At the first meeting, Stein peppered both Smith and Levie with questions about the company, business model and more. By 2 a.m. the next morning, Stein received a multi-page response from the team with thoughtful, detailed responses to each questions. He saw this as a good sign. “There was an intelligence, an energy and drive in Aaron and Dylan that was immediately apparent. That’s not always the case int he valley,” he says.

And when evaluating whether to invest in the company, he thought that the product served a definite purpose in the business world, but had what he called “modest aspirations,” for Box. DFJ signed off on the investment and by July 2006, terms sheets were signed and Box had raised $1.5 million from the firm.

Consumer To Enterprise

Interestingly, it was Stein who helped define a set vision for the company in its early days. Box, at its start, was focused on both consumers and businesses, offering a dead simple way to store files. In 2006, the company continued to iterate on both sides of the business, launching file sharing options for consumers and businesses. But Stein, who was an active part of Box’s business (and served on the board), saw the writing on the wall that enterprise customers were “stickier,” in his words, and pushed the company to “sharpen its focus.”

Even Levie admits that he didn’t grasp how large and substantial the enterprise opportunity was until Stein started pitching him and Smith on a more targeted product. He explains, “Josh Stein started to connect the dots on doing an SaaS enterprise model. We credit him to being able to shine light for us on something we couldn’t see.”

The company began tailoring the product towards business users around 2007, and as Stein says, “engagement went through the roof.”

Another added feature which helped boost enterprise use was security, which was added in 2008. The company found that businesses were willing to pay even more for added security and permissioning. While not the sexiest product feature, the ability to have administrative control over data was really a turning point for product, says Stein. The addition of admin controls and security played into the needs of big companies, and CIOs started to actually pay attention to Box.

It was these offerings that caught the attention of Justin Slaten, Director, Information Technology for Wasserman Media in 2007. “There were lot of companies popping up at time that were consumer facing products in file storage but weren’t focused on the enterprise,” he says. “Box was the first company that was willing to offer a product that focused on business users.”

Nearly six years later, Wasserman is still using Box (along with Procter And Gamble, Pandora, Skype, LinkedIn, Turner and many others). Slaten says that Box is “in tune” with what clients want in a user experience, whether that be collaboration, apps or security. “They are always deploying features that I actually want,” he says.

By 2008, the company still had just a handful of employees but Levie and Smith were both settling into their defined roles within the business, with Levie as CEO and Smith as CFO. As Stein explains, the founders’ strengths were complimentary from the beginning. “Aaron is focused more on the product, design and technology part of the business and Dylan is drawn to the economics and business model. These defined skill sets allowed them to focus on building business and think about it holistically.”

Not only did Smith and Levie work days and nights together, but they were also room mates and actually lived at the offices until 2008. The company eventually moved to Palo Alto shortly after the DFJ funding round, and the Smith and Levie took a loft above the office, which had just a few mattresses on the floor.

Living and working together usually doesn’t work for most founders, especially when they are actually sharing a bedroom. But Smith explains that they developed systems early on to be able to live with each other, calling Levie more of a brother than a friend.

From A Berkeley Garage To A $600 Million-Plus Dollar Business

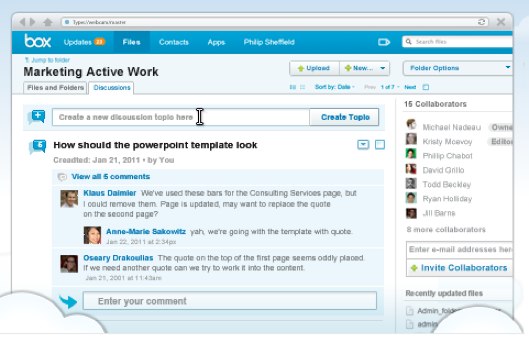

As competitors started popping up in 2007 and 2008, Box focused on strengthening its enterprise product even further. Box steadily evolved into more than just a file storage platform, becoming a full-fledged collaborative application where businesses can actually communicate about document updates, sync files remotely, and even add features from Salesforce, Google Apps, NetSuite, Yammer and others. Mobile is another area where Box has been focusing, adopting HTML5, launching iPhone, iPad and Android apps and more.

Along the way, Box realized the market was much bigger than file storage. As it evolved into a collaboration platform, the company realized the enormous opportunity in providing a simple, cloud-based alternative to legacy systems like Microsoft Sharepoint. The company began aggressively campaigning for existing Sharepoint users to make the switch.

Stein says that in 2009, he realized that Box was going to be a multibillion company. “You could see acceleration of taking off. In 2010, the company doubled the amount of sales reps selling the product to businesses and sales and productivity skyrocketed.”

Around the same time, Box raised $15 million on Series C funding from Scale Venture Partners, DFJ and U.S. Venture Partners. A year later, Box landed $48 million in new funding from Meritech Capital Partners, Andreessen Horowitz, Emergence Capital Partners, DFJ, Scale Venture Partners and US Venture Partners.

And then the acquisition offers started coming in. As reported last year, the company fielded a $600 million acquisition offer from Citrix, exactly 6 years after raising $350,000 from Mark Cuban.

While Levie tends to shy away from commenting on the acquisition, we heard from sources that it was a hard decision to say no to. There was a lot of money to be made, and it was a risk to keep pushing forward as an independent company.

“I think you get these opportunities once every decade where such a massive change is happening in the landscape that enables a startup to be at the center,” says Levie. “And there is a lot of pressure to make sure you build something successful when making the decisions to stay independent.”

When making the decision to turn down the acquisition, Levie and Smith both had the sense that Box’s story wasn’t finished. The company was still growing rapidly, churn rates were down, and customers were actually renewing for additional paid plans, all leading to a healthy, fast-growing top line.

Turning down the acquisition was a very clarifying experience for both investors and Box’s founders because it set a clear goal for the company. The expectation was at the time was that if Box stayed independent, the company was going to really go for it, with the goal of eventually becoming a public company.

At that point, it made sense for Box to raise another round, with this one totaling $81 million. Investors included Salesforce.com, SAP Ventures, Bessemer Venture Partners, NEA, Andreessen Horowitz and DFJ.

As for going public, Levie says that inevitably employees and investors will desire liquidity and being a public company afford this opportunity.

Stein echoes Levie’s thoughts, and believes the company is in a prime position to be a public company. “Enterprise SaaS companies are perfectly suited to be public companies. The company’s gross margins are north of 70 percent and there’s recurring revenue, which is great for the public markets,” he explains. “I think Box is the kind of company we see once every decade at DFJ. I compare it to Salesforce but I think Box is actually creating an even larger category of enterprise software. I think it has the potential to be the next email; basically what company intranets are supposed to be.” he says.

As for revenue, Box is on track to triple revenue in 2012. Last year, Box reportedly brought in around $25 million in revenue, so we’re looking at a $75 million-plus sales number for 2012. Smith adds that the company is growing faster than they ever have in the past.

The Enterprise Culture And The Competition

Running an enterprise company presents its own unique challenges. Levie says one of his biggest challenges is developing easy to use products for businesses, and iterating fast, despite being an enterprise company. “Our engineers have to be consumer internet minds, our products have to be consumer minded, we have to move fast but build software like an enterprise company,” he says.

Levie explains that each week, Box re-releases the site with fixes. He compares this to the yearly cycle for products builds for on-premise companies. But he sees the rapid product iteration of consumer focused companies like Facebook, as the future of enterprise and cloud.

“IBM, Oracle and Microsoft are always going to respond more slowly to market. They haven’t developed a rapid release product development strategy. So how we compete is moving more quickly, and being more agile. We can reach and get end users faster than the bigger player. The next generation of enterprise software companies will be organizations built like consumer internet companies that happen to sell to businesses,” Levie comments.

But the challenge to producing fast, and adding features is taking business customers off guard as well as education. For us to flip a feature through quickly, it has to be additive, Levie says. “We can’t impair the customer’s processes and this is a constant tension.”

Competition has also come recently from Google with the launch of the search giant’s own storage product, Google Drive. Levie doesn’t seem to be too worried to call Google a competitor. “I can’t think of a single startup that won’t have Google as a competitor. For same reason Oracle could never build a great consumer product, I think it is hard for companies like Google to be a leader in the enterprise.”

Another challenge, though unsurprising, is hiring, particularly in engineering and sales. As Box’s COO Dan Levin explains, the company needs to find people who are not only good at their job but also reinforce the entrepreneurial, product-driven, fast-paced culture at Box. He says that Box roughly phone screens 100 people to find ten to interview on site to make 1 to 2 offers.

And Box is continuing to staff up. Levie says the company is looking to boost headcount by 50-75 percent by the end of the year. Currently, Box has 425 employees and just moved to new headquarters in Palo Alto.

The Future

Levie recalls pitching Marc Andreessen a few years ago on investing in the company’s Series D round. He had put up growth projections and goals for Box, and while Andreessen said this data was positive, he asked Levie a thought-provoking question. “How fast does the storage market have to grow to get to these goals?” It’s a question that Levie continually repeats to himself when making projections for the future of Box.

Levie sees Box’s future particularly centralized around creating an ecosystem of apps both on mobile and web platforms. Last fall, Box launched a platform for developers building off of the Box platform, called the Box Innovation Network (/bin). And earlier this year, we learned about Box OneCloud, a mobile cloud and API for the enterprise that allows businesses to access, edit, and share content from their mobile devices.

Box is also looking to use data to help businesses make better business decisions. And adding new applications to the Box platform helps bring more data into the collaboration flow. “We want Box to be the foundation for storage, permissions, collaboration, security, with horizontal apps built on top of the service. We think we can be an important broker for applications to generate business and demand,” says Levie.

Smith adds that Box also plans to build data centers in additional countries in the world, and sees international markets as a huge growth area for the company.

A few years shy of their thirtieth birthdays, Smith and Levie are at the helm of one of the fastest growing enterprise startups in the technology world. And the company is fast approaching a billion valuation, if it hasn’t reached that already. Box’s story isn’t an overnight success but more of a testament to the strength of having two, passion-driven founders who weren’t afraid to cold-call well-known investors, drop out of college to live the startup dream, and squander thousands in poker winnings on a fledgling idea.