It transpires that the government of Nunavut, a remote territory of Canada between Hudson bay and Baffin bay, recently acquired some new digital cameras for the purpose of creating driver’s licenses. The files created by the cameras, presumably a handful of megabytes unless they’re using Hasselblads, were too big to be effectively emailed for processing due to the extreme limitations of internet connections in the area. Instead, they were loaded onto flash drives and flown hundreds of miles to Iqaluit, where they were processed and returned.

Of course, the first thing that comes to mind is jokes: haven’t they heard of “save for web”? Did they try the wi-fi at the coffee shop? And in the frozen tundra, shouldn’t they be issuing sledging licenses? But the truth is that this rather absurd little situation is just one of thousands in which huge swaths of the world are being left behind in our rush toward connectivity. While the haves are complaining about losing 4G service when they’re in their apartment, the have-nots are paying hundreds of dollars for speeds we would have laughed at ten years ago. Is it possible to bridge the gap, or are the Nunavuts of the world simply out of luck?

Begging the question

Practically speaking, it’s easy to dismiss the issue entirely by making some noises about how living in the sticks is a choice, and the physical isolation is a natural match for informational isolation. You see pictures of a llama farm in the Andes or an Inuktikut native in Nunavut, and you think “do these guys really need broadband?” There’s a grain of truth to this, but really it’s a form of entitled bigotry and a refusal to acknowledge the purpose of civilization, which (briefly stated) is to grow and improve human communities. Cities don’t “deserve” broadband any more than the some ice-encrusted region with more bears than people.

Besides, problems are interesting. And solutions have a tendency to breed other solutions. Finding a way to serve remote areas with real and affordable broadband could easily yield serious improvements to the efficiency and reach of our existing and future networks. This isn’t about just buying enough copper to lay down cables to every home in the arctic, it’s about acknowledging limitations in our current systems and thinking about whether those limitations are something we want to work and live under. But there are very few limitations that people will truly accept as permanent.

The cost of not doing business

It should probably be acknowledged up front that nobody is going to make any money providing remote areas with internet. Profit is a powerful motive, and it is completely absent here, at least on the face of it. Companies like Comcast and Hughes exist to make money; it just so happens that they make money providing connectivity. National and local governments, however, serve the people, and part of their mandate is the standard of living. The absence of a working internet connection, or at least the absence of one that belongs in this decade, is a serious problem in that category of government responsibility. The Artic Communications Infrastructure Assessment report (which inspired this article) makes this point very clear.

India is about to invest some 20 billion dollars into a huge roll-out of broadband services. A huge amount of this will be going to foreign contractors, who will be thrilled to be laying their own style of foundation in a market set to explode. The situation is, unfortunately, somewhat different in places like Nunavut. The population of the entire territory is around 35,000 people. If it were a country, it would be the 15th largest in the world by area. Subtracting the ~6000 people who live in the largest city, Iqaluit, you have on average one person for every 28 square miles. In Bombay, the number of people per square mile is over 50,000.

Resistance

In Canada, there has actually been a lot of discussion on this topic. The northern territories make up only a tiny fraction of the population, and a tension exists between the south and the north as to just how much the big cities should be subsidizing the rural areas. The Canadian telecoms regulatory agency, the CRTC, actually put together a requirement that the existing telecoms should establish a “deferral account” by skimming money from their subscriptions in urban areas (high-profit, low-cost), 95% of which was to be used for remote and rural connectivity (the remaining 5% would go to accessibility for the disabled).

But lacking a specific spending plan, the money just piled up. Maybe $670 million was set aside when someone questioned the jurisdiction of the CRTC over things like expanding broadband access. Some people wanted the money to go back to the customers. Some questioned the legitimacy of requiring urban users to subsidize rural areas.

It seems a little misguided to me that such a war chest should be squandered on a one-time refund to customers, or spent on areas where the telecoms are already voluntarily investing billions. But there you have it — it’s the kind of questionably justified resentment that some people feel when they see the amount of their paycheck that goes into Medicare or Social Security.

It’s not big big money, as far as government spending goes, but half a billion dollars sure isn’t small money, either. And as we have seen, it presents a kind of ethical quandary: can we justify spending that much money so a few people in the sticks can check Facebook?

It’s more than that, though: without modernization in this area, services that increasingly rely on connectivity as an adjunct to their functions (licensing, law enforcement, hospitals) will suffer and the standard of living will truly be lower. So I think the answer is that at some point, we’re going to have to. And by the time you have to, you always wish you’d done it earlier. So what are the options?

For Nunavut and places like it (rural Russia and China, developing regions in Africa and India), options are actually very few when you get down to it. The combination of extreme isolation and environmental conditions makes for a logistical nightmare.

Solutions

If the town is lucky enough to be in range of current data-serving satellites, which understandably mainly orbit in range of the more habitable zone of the planet, you can install a base station. The trouble is that these are expensive to install and upgrade. The stations serving Nunavut now are slow enough that sending photos was impractical, and even slight population growth would instantly render the bandwidth totally inadequate. What if a refinery were to be established, and a few hundred people move into the area? All of a sudden that seven-year-old base station, barely sufficient for a population of 50, becomes absurd. And all of a sudden, that location becomes a risk because critical services can’t be reached during, say, inclement weather, which may be when they are most required.

You could establish a series of relays bouncing signals from a central area connected to a backbone. This is common practice elsewhere, good for getting a signal from downtown to the suburbs, but in a places where the hub is separated from the other points by miles of rough territory, it becomes problematic. After all, the towers can only be so far apart, and require regular maintenance. In Nunavut you’d have to have someone going around knocking the ice off the dishes so they don’t collapse. Not a job I’d volunteer for, and not a sustainable or affordable model. Besides that, it would be extremely costly to radiate these tower relays to every far-flung community.

The only solution seems to be industrial-sized. In coastal communities like Nunavut, an undersea cable seems to be the tool for the job. But inland areas would need a buried cable. To future-proof it a bit, it should probably be fiber, not copper. I don’t even want to estimate the kinds of costs it would take to put three or four thousand miles of fiber under the ground, with repeaters, protection, maintenance roads, and so on. To be honest, that $670m figure saved by the telecoms starts to look like a down payment.

But what other option is there? Connectivity is a necessity these days for prosperity. Without reliable internet, one is limited to places one can reach physically, which in rural areas may not be more than a few hundred or thousand people in a handful of towns. With reliable internet, the possibilities expand almost infinitely. Education and social awareness increases, and people can become involved in industries that require nothing but data to be exchanged — which makes up quite a lot of the economy these days. Some growth might be achieved by putting a little money into fishing or mining, but it’s nothing compared with the opportunity to take part in the world’s “virtual” economy, larger and more real than any local economy.

Necessity

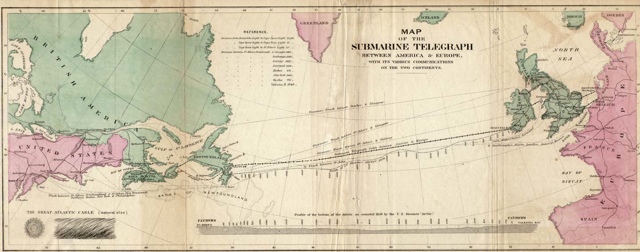

It’s a problem without a definite solution, currently, but so was getting messages across the Atlantic in good time, until someone took the trouble to sink a telegraph cable between Ireland and Newfoundland. This is one of those problems with continental scale.

Who will volunteer to undertake this enormous task? At this level of investment, it’s too great a risk for any one entity to take on alone. Google, for instance, isn’t going to just say “all right, we’ll build that billion-dollar fiber backbone for Africa.” And neither is the African Union, which likely has more important things to manage. And neither is the government of Canada, apparently, until absolutely necessary. Australia, on the other hand, is spending billions per year to establish high-speed internet in its most remote regions.

One option might be an international fund being contributed to by ISPs and telecoms; Canada alone raised half a billion in a few years on the subscriptions of perhaps 15 or 20 million people. A similar requirement in the US and other rich, connected countries, guaranteeing a certain level of outlay for the establishment of remote networks, would produce a very substantial sum of earmarked money. The telecoms would fight it, of course, but the deal could be sweetened with low-interest matching loans or what have you. I’m not a politician, if that wasn’t clear from the get-go, and I’m sure this idea of an international fund is astoundingly naive in many ways. But I can’t think of another way to advance the state of global connectivity, such is the size of the problem.

Right now there are thousands of communities like Nunavut, underserved and perhaps in danger of being extinguished through neglect. As Nunavut found, the internet is quickly changing from a convenience to a necessity. Not that even necessities are guaranteed by the government or global community — but it means something to class basic connectivity among such other basic public services as medical care, clean water, and police and fire departments.

It may be that research is underway that will make laying fiber or cable seem positively primitive, but I doubt there’s anything in Alcatel-Lucent or Cisco’s labs that’s going to obsolete basic broadband infrastructure. And skimming the income of an industry already in rapid expansion internationally seems a timely solution, however unpopular it may be among the carriers.

The internet is a promise. A promise that physical distances will be rendered irrelevant. At the moment that promise seems only half fulfilled, as the internet is limited by, of all things, physical distance. The world will be connected, though it be at great cost. Such has always been the trend. But those who would pay the greatest cost, as usual, stand to gain the most by it. They wouldn’t agree to it any other way, though a little coercion is sometimes necessary.