The rising number of cameras recording activity on the street and on the job makes for an interesting new set of problems. I examined a few in my Surveillant Society post, and one has just emerged that could set a serious precedent for the application of tech in criminal cases.

On September 25, an Oakland police officer pulled over a car and the suspect got out and fled. The officer chased him, and during a struggle the suspect was shot and killed. The charges, suspect’s and officer’s names, are undisclosed but it was stated that the suspect was armed with a gun.

It would be another sadly typical escalation with a lethal end, except that the officer in question had at some point flipped on his “chest-cam,” a relatively recent development in policing where a Flip-type pocket cam (in this case a Vievu model) is attached to the uniform and turned on under certain circumstances. The presence of this camera is leading to a few potentially major legal questions given the stakes of the case. While some are more legal than tech-related, it’s worth taking a minute to see how technological advances are shaping criminal law.

First, when are officers required to activate the camera? There are rules in the department that govern when you should, should not, or must turn on your camera, but failure to do so (innocent or deliberate) can easily be explained, and events not categorized as “stops and arrests” could need recording. In Surveillant Society, I note that the inevitable end of cameras in situations like this is to be recording all the time, recycling their footage as they go, and indeed dash and security cameras (not as limited by size) already do this. In that situation, the footage would be recorded regardless of the officer’s actions, and collected later. Unfortunately battery and storage constraints prohibit this simple solution for now. In the meantime, the regulations regarding recording should be public information (I’m sure they are already) and anyone in any encounter with an officer should be able to request that the camera be turned on.

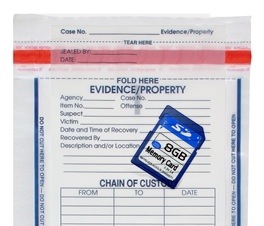

Second, how is the footage handled? That is to say, who has access to the footage and how is it kept safe from tampering? The answer is probably to say that it must be treated as any other material evidence would be: bagged, logged, and kept centrally and securely; there are already plenty of regulations to this effect, though they aren’t always respected. And unlike physical evidence, the footage on the camera has the potential to be duplicated, which means it could be given to someone without affecting the original. SFGate asks whether the video should be provided to the press, but I don’t see any reason why it should be (or rather, why it should be treated differently than a weapon or suspect ID) during an ongoing investigation.

Second, how is the footage handled? That is to say, who has access to the footage and how is it kept safe from tampering? The answer is probably to say that it must be treated as any other material evidence would be: bagged, logged, and kept centrally and securely; there are already plenty of regulations to this effect, though they aren’t always respected. And unlike physical evidence, the footage on the camera has the potential to be duplicated, which means it could be given to someone without affecting the original. SFGate asks whether the video should be provided to the press, but I don’t see any reason why it should be (or rather, why it should be treated differently than a weapon or suspect ID) during an ongoing investigation.

Can the officer in question view the footage before giving a statement? The prevailing opinion seems to be that no, this would be unacceptable, and I agree. The statement of a witness or participant in a crime must be from memory. It is up to the judge and jury to determine the level of truthfulness; if a suspect (or officer) is aware that their actions are on video, it’s very possible their statement will change to reflect that. Furthermore, if they actually see the video, it will change further. The documentation of a police encounter is as much for the department as it is for the accused. Certainly the video would be brought in as evidence and those involved would be given a chance to explain their actions during cross examination or when otherwise prompted.

The officer’s attorney notes that some departments have actually answered the above question in the affirmative, with unions pushing for the ability to review footage before making a statement. But, she says, “it’s hard to have a hard-and-fast rule in terms of these videos. Every situation and every officer is very different.” Unfortunately, a hard-and-fast rule is necessary, and the nuances of enforcement and compliance must be worked out in court.

At what level should this kind of tech decision be legislated? The inevitable civil rights violation might go all the way up to the Supreme Court a la Miranda, but differing resources, constituencies, and policing strategies may make such high-level restrictions impractical. I would say that some Supreme Court decisions regarding the application of civil rights to new tech will be necessary, but that regulations will have to be enacted at the state level, and then more specifically at the department level, where they will need to be made as simple and transparent as possible and probably added to the standard statements made by cops during bookings and arrests. “Video of this encounter can and will be used against you, and me, in a court of law.”

We all see how tech affects us in everyday life, but the institution of law is a much slower-moving creature, and even when something major occurs (like the purchase of hundreds of cameras for installation on the persons of officers), the consequences likely won’t be fully felt for years, and even then they will likely be felt as part of a tragedy or injustice. As a theoretical source of accountability, these cameras are invaluable, but as usual we are more likely to learn that through the publication of criminal acts rather than the confirmation of virtuous ones.

[via Reddit]