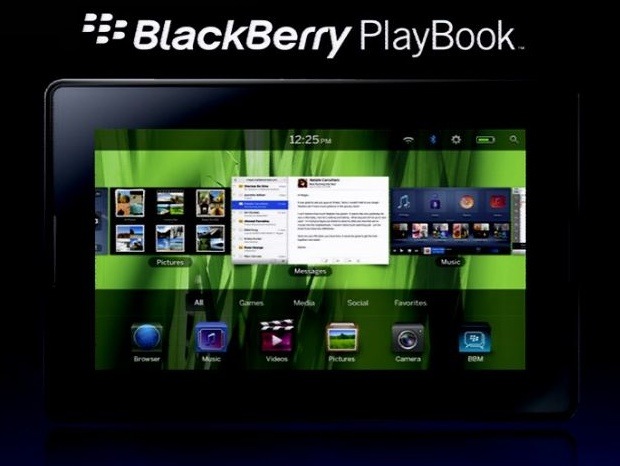

I’ve been using the Blackberry Playbook since Friday and I find it to be a unique and very usable device. The obvious problems aside – no native email client, poor browsing, wonky Flash support – it’s clear that RIM took lots of care to produce a device that would appeal to their core audience of crackberriers. Even the ill-advised Blackberry Bridge makes a certain kind of sense. Why? Because the removal of all points of security failure from the tablet gives the folks in IT a reason to OK the device on their networks. The same can’t be said of any of the other tablets, iOS and Android devices included. In fact, without the Bridge the Playbook is a simple and compelling media consumption device.

But Blackberry is now trying to survive a period marked by a rapid and permanent change in smartphone usage. Back when Blackberries were pagers, the best a business user on the road could hope for was a fax sent to a hotel room. A few short years later and Blackberry ruled the mobile messaging space. Their email product and messenger allowed countless people to remain connected everywhere, at all times, an accomplishment that brought about a sea change in the way we interact online. The Blackberry is a unique artifact that defined how a generation lived and worked. Blackberries made it OK to be always on call, much to our own detriment.

Then came the Sidekick. That phone, and its successors, changed how a generation played. Email and messaging on a phone quickly became de rigueur and, ultimately, a non-feature.

So now Blackberry’s most significant feature – email – is no longer very interesting. The squat, keyboard-centric devices are competing against devices of all shapes and sizes and Blackberry is losing.

According to IDC, RIM shipped approximately 48.8 million units worldwide, followed closely by the Apple’s 47 million. To put this into perspective, Nokia sold 453.0 million phones (not smartphones in particular, but total units) and Samsung sold 280.2 million (same caveat). To put it further into perspective, Apple has only been selling iPhones since 2007 while RIM has been selling phones since 1999. RIM’s smartphone market share is down from 34% to 29% in North America. And even newer contender, Android, is also taking its toll, though tracking it and its effects isn’t as straightforward.

When RIM CEO Mike Lazaridis flaked in a BBC interview, you could see a CEO at wit’s end. His product is, at best, a strong but uninteresting runner in a crowded race. Rather than outpacing the competition, however, RIM is barely keeping in stride. His claim that the phone is popular with “businesses, leaders, celebrities, consumers, and teenagers” is, in one sense, true. But any phone manufacturer can claim the same thing and be perfectly right. There are so many phones sold daily that RIM’s products are now a drop in the mobile bucket.

RIM is the next Nokia: an iconic company laid low by an unwillingness to adapt its products. It’s not pretty to see this happening to what is certainly a classic and influential device but even the Playbook, as unique as it is, won’t change customers’ perceptions of RIM. Claim all the brand loyalty you want here, but consumers have so much choice on so many fronts that even statistically RIM won’t be able to outsell their competitors. As Nokia learned far too late, it doesn’t make any sense to cling to old paradigms and rely on old strengths.

Do I want RIM to go away? Absolutely not. They produce excellent products. I love the interface and the design. However, when their most interesting device, the Playbook, refuses to play to the simple needs of the general consumer and maintains a dedication to a shrinking business fleet base, it’s time to rethink RIM’s place in the mobile ecosystem. It is my honest fear that RIM, like so many companies before it, will find that ecosystem more and more hostile to their unique product.