What happens in Vegas no longer stays in Vegas.

What happens in Vegas no longer stays in Vegas.

Where once it was possible to fly to the middle of the desert, get absolutely wrecked on frozen margaritas and warm hookers and then return to civilization as if nothing had happened, today it’s impossible to so much as open a minibar here without someone taking a photo and broadcasting it on Facebook. Savvy to this new reality, even the most shitty hotel on the strip – which is to say, The Riviera – has a Twitter account.

And yet, despite the millions of tweets and status updates that flow in and out of Sin City every weekend, Vegas remains a town to which technology simply cannot do justice.

For a start, the hotels are temples to physical spectacle, filled with gigantic fountains, exploding pirate ships, gondola rides, showgirls, lions and tigers and reproductions of Michelangelo’s David (oh my). Every bar and casino has a theme – from Jimmy Buffet’s Margaretaville to the preposterous Pussycat Dolls lounge in Caesars Palace. You could spend all day watching clips of this stuff online without even starting to understand what it’s like to be here.

Even at the seediest end of the market – which is to say, the sex end – where, traditionally, analogue pleasures; strip shows, adult theaters, even hookers – have lost market share to Internet porn viewed in the comfort of one’s own home, the Vegas sex industry continues to thrive. “Passers” – commission-paid workers handing out flyers for escort services – line the strip, sometime three deep. Every casino worth its salt has a topless review and, of course, Nevada is the only state to offer legalized brothels.

To paraphrase a travel-writing cliche, Las Vegas is a city of technological contrasts. Nowhere else on planet earth understands more effectively how to harness technology in order to deliver overwhelmingly physical experiences. And in Las Vegas, no experience better demonstrates that tech-reality hybrid than Cirque du Soleil’s ‘KÀ’.

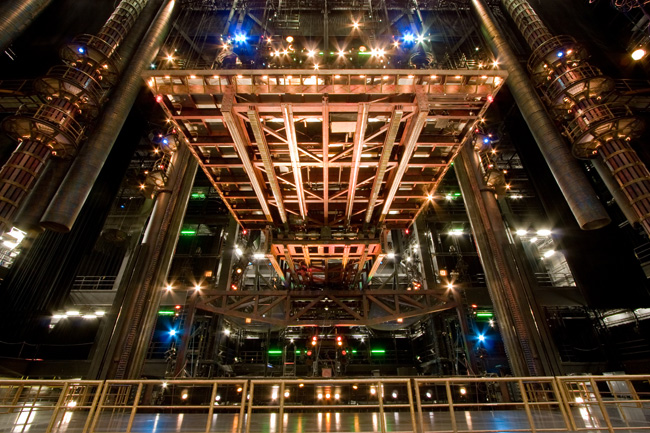

Go watch this video clip from the show. It’s incredible: two giant movable stages move above a gaping void; the main stage (“the sandcliff deck”) rotating from level to vertical and back again while a cast of characters jump and dance and spin and fly on, below and above it. The Los Angeles Times said the show “may well be the most lavish production in the history of Western theater. It is surely the most technologically advanced.” Jim Hutchison has some amazing photos of the sandcliff deck, and the rest of the set, here.

But nothing on YouTube can possibly do justice to how it feels sitting in the audience during a performance. Each seat has two speakers built into the back to provide the deeply eerie effect of being surrounded by voices and noise throughout the performance. The entire auditorium is ringed by towering metal gantries, columns and walkways on which, before and during the show, characters stand, shrieking, yelling and playing drums. None of that, though, distracts from the sheer balls-out awesomeness of seeing the giant mechanical stages doing their thing.

For a start they move silently – it really is as if they are floating in space. And the physical changes they undergo through the show – flat and covered in sand one moment; a vertical cliff face the next (hence “sandcliff deck”) – is more magical than anything David Copperfield ever managed to pull off. At one point in the show – just because it can – the entire stage turns into a kind of gigantic Microsoft Surface, on which – still vertical – the cast perform a fierce battle scene with horizontal and vertical running, jumping and flying. Each time a character lands, the stage explodes with light and colour. Oh, and then there’s an “arrow” scene, where archers standing on a gantry fire arrows into the vertical stage; arrows which then act as climbing pegs for characters to scale the wall, before jumping 70 feet into the void.

Two years ago, I described seeing ELEW playing piano live on stage in San Francisco, and how it underscored for me the thrill of live experiences — and how those experiences will never, ever be replaced by technology. KÀ gave me the same thrill, but with the added bonus of seeing the amazing potential for technology to augment live performance. The technology in KÀ delivers real-world experiences that would have made our theatre-going grandparents’ heads explode.

And then things got way, way more interesting.

I guess someone at Cirque du Soleil is a fan of TechCrunch because, a few days after I arrived in Vegas, an email arrived from KÀ’s publicist, Jeff Lovari, inviting me to take a “TD tour” of the show. Which is to say, a backstage tour, during an actual performance, lead by KÀ’s technical director, Erik Walstad.

Hell fucking yes.

And so it was on Wednesday of this week, I found myself standing several stories below seating level, watching a succession of the world’s most talented acrobats jumping 70 feet from the top of a floating stage and landing on giant airbags not two feet in front of me. To explain everything I saw during Erik’s 90 minute tour would probably take me a dozen posts. Instead I’m going to try to cram it all into two: starting here will a few of the raw facts, and then followed up next week (schedules permitting) with a video interview with Erik in which I’ll ask him to explain exactly how everything works.

Ok? Ok. Here we go…

KÀ took almost a decade from conception to completion. Prior to the show’s opening, the stage from the previous show (EFX) was torn out and then the entire inside of the MGM Grand’s theatre was demolished, leaving just the walls standing. Then diggers excavated a pit deep into the ground to make way for the show’s main “void”, and the years-long task of constructing KÀ’s enormous set could begin. The distance from the lowest depth of the void to the highest point of the “grid” from which acrobats jump, fly and bungee, is 98 feet.

The main sandcliff deck stage weighs 50 tons and can rotate 360 degrees and tilt from flat to 100 degrees. Watching the stage move from backstage, you’re struck by the amount of noise it makes: it’s virtually silent, a feat achieved by housing all of the hydraulic machinery on the roof of the building.

The lengths taken to ensure the safety of performers are so extreme that they’re almost comical. At the start of the show there’s a brief scene where a cast members walks from one end of the stage to the other. To the audience, it appears like the safest feat in the world – the front of the stage is maybe two feet from the ground. If, however, they could see behind the performer, they’d realize that the drop on the other side of the stage is closer to 20 feet. As a result, as the performer walks, a series of hidden airbags, like those used by stuntmen, inflate and deflate to provide a cushion should he fall. It’s kind of amazing to watch, a bit like Penn and Teller’s classic Sleight of Hand Explained routine.

Whenever performers are on any of the gigantic floating stages, an array of airbags – supported by two giant nets – sits up to 70 feet below them, ready to catch them when they land, either deliberately or (rarely) accidentally. Traditional safety nets can’t be used on their own because the performers are falling so fast, they’d simply bounce right back out again.

Due to the large number of performers jumping and landing in quick succession, each airbag consists of a number of separate cells, each of which can inflate and deflate independently. When a performer lands, air is forced out of their target cell, which is then instantly re-inflated allowing the performer to stand up and walk away. At some points in the show, this happens several times a minute.

In case the power should fail during a show, each of the airback pumps has its own uninterruptible power supply, good for half an hour, ensuring a safe landing even if all else fails. “Half an hour is probably enough time for someone to land” says Erik dryly.

The arrow scene, where the sandcliff stage becomes a vertical climbing wall, is a variation of the old carvinal knife throwing trick. When each archer fires his dummy arrow, a matching “arrow” is propelled out of the walls’s surface, giving the illusion that it has hit its target. A little puff of “dust” completes the illusion. After that, though, things get more complicated as performers climb up and down the arrows while more arrows land and others disappear. To ensure the performers’ safety, each arrow (or “peg” as they’re called) contains a sensor which prevents it from shooting outwards if someone is standing or laying on top of it (“otherwise they’d be impaled, which would be bad”). Likewise, the pegs can only contract with less than 20lbs of pressure, so if a performer is still hanging off one, it stays put. And if all that wasn’t enough, the wall also contains a bank of “emergency pegs” which can be shot out to form an escape ladder/bridge if anything goes wrong.

Meanwhile, high about the stage, the technical team has come up with some other neat safety innovations. In the event that a wire or harness malfunctions, leaving a performer swinging above the audience, a fail-safe device automatically lowers them down over an aisle. “Otherwise we’d have to evacuate the whole auditorium to rescue one performer”.

Each second of the show is perfectly choreographed, with a stage manager calling every cue: every inflated and deflated airbag, every jumper, every movement of the stages. I wore an earpiece during the show and the level of calmness in her voice – as theatrical chaos reigned on stage – was impressive. Even more impressive was hearing cues being given to performers who were in the middle of stunts: many of them wear earpieces too, so they know when it’s safe to perform certain jumps or falls. If you’ve ever watched air traffic controllers at work at a busy airport, you’ll have some idea of the concentration and coordination it takes to call a Cirque show.

The KÀ Theatre seems like a world of its own, but it’s still connected in to the MGM fire detection system. Before every pyrotechnic stunt, the stage manager requests that MGM’s fire officer temporarily override the fire detection equipment in the theatre for the duration of the stunt; then it’s switched back on. This happens three or four times in every show. Because fire detection can only be overridden before a fire is detected, if someone actives a fire alarm anywhere in the shops or restaurants surrounding the theatre then all of KA’s pyrotechnic effects have to stop. Given that the closing of the show is a huge firework display, this can be something of a problem.

For all the years of technical planning that went in to building the KA theatre, the designers only thought to include one stage elevator. As a result, technical staff and performers alike have to share the same elevator during the show. At one point of the tour, Erik and I shared an elevator up to the aerial grid with a gigantic man dressed as a warrior. It was a little weird.

Ok, that’s all for part one. In part two, I’ll sit down with Erik and have him explain the finer technical details of how thew show works, how he became involved with it, and also – possibly – his love of traditional British narrowboats.

Tune in next time.